Being a better listener is a key skill for nearly anything you want to do. The better you are at listening, the better you can be as a friend, a partner, a colleague, and so on.

But listening is hard. We’ve all got a lot going on. Ideas pop in and out of our heads, and we often feel like we’re just South of where we need to be — we’re not quite caught up. As a result, our minds are rarely still, empty, at ease. When our minds aren’t at ease, we do a terrible job of listening. When we do a terrible job of listening, we end up doing a terrible job of thinking as well.

So here’s a trick you can use to improve your listening. It involves using your the psychological tools that have been shown to be most effective for memorization: visualizing and spatial thinking.

The Listening Palace Trick

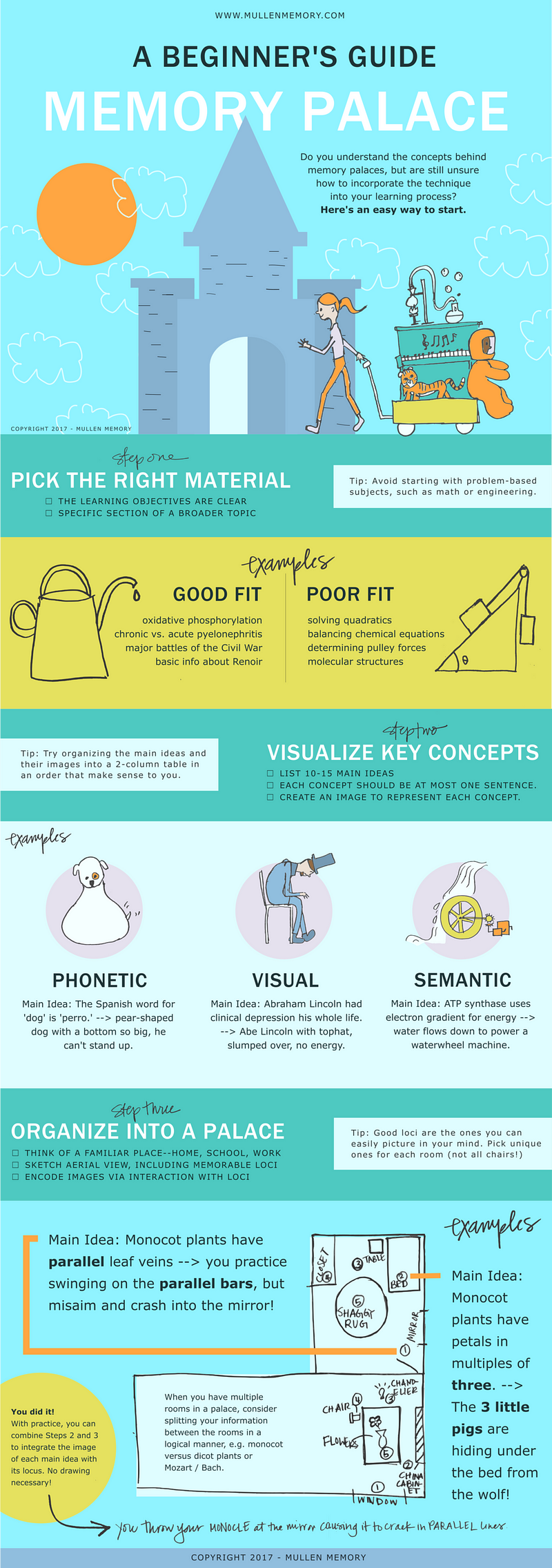

The next time someone starts relaying information to you, get yourself into a mode of thinking much like what world memory champion Alex Mullen (and many others, as well). It’s called the memory palace. Below is a cool infographic on the concept.

The basis for the trick is simple: use your mind’s ability to spatially separate and retain things in order to store information for later use and retrieval. Place bits of information in different parts of a place you’re familiar with (like your home), and recall what is in each room.

This technique works wonders for people in competitive memory competitions, where lists of names, numbers, or words are thrown out for participants to memorize and spit back out. In fact, that’s where it became popular.

But listening comprehension is a whole different ball-game. Most people are not talking to you by reading from a list of the important information they want you to retain. They speak in stories, they think out loud, the double back and change their stories mid-stream. It’s not easy to listen and comprehend.

What I’m suggesting is to use that for listening — staying focused on what someone is saying, and pulling out the vital information.

How To Do It

The first thing to do in order to more effectively listen is to figure out what the purpose of the conversation is. In a lot of cases, this can be done before the conversation takes place. There are a few main reasons why a conversation is going to happen. Someone either wants to:

- make you aware of something

- get your feedback

- get you to do something

- vent/think through something out loud with you

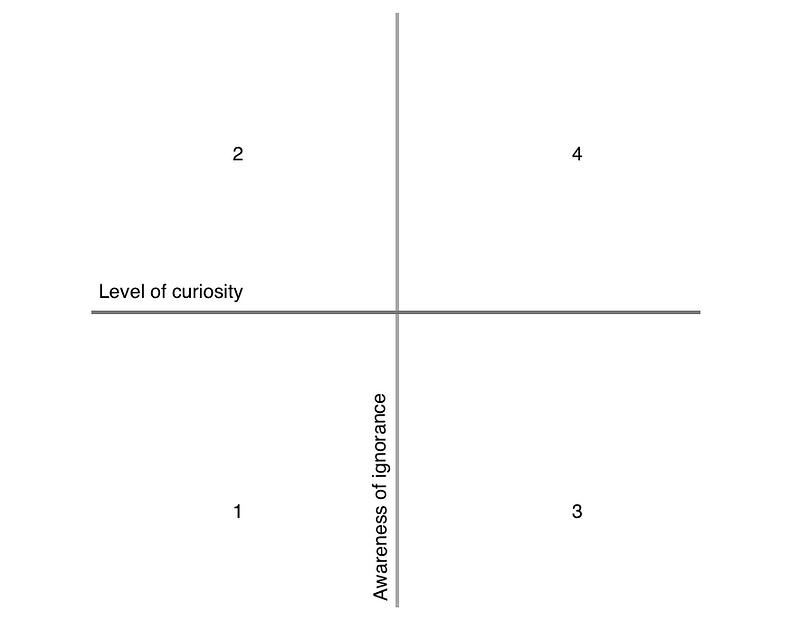

Once you have figured out what the purpose is, you can place that purpose in the main entrance of what I’ll call your “listening palace”. It’s the place you want to get through after all of the wandering through the palace. Once the conversation starts, envision that main point right there in front of the door, ready to go outside.

As the other parties speak, and bring up other points or people, put those things in rooms of the palace. When people are described during the conversation with adjectives, place them in the room acting out that adjective. The same is true when you hear about two or more people having had an interaction. Place them in a room with each other, interacting.

As the conversation yields more points, includes more people, and reveals more ideas, arrange them in the various rooms. Also, try to place them closer to or further away from the front door based on how vital you see them to the main point of the conversation (which can also change).

The great thing about doing this while you listen is that it then helps you to come up with really good clarifying questions. As you visualize information and try to couple it with other information, or place it in relation to other information, you’ll naturally have questions about how it comes together. Ask those questions, and get clarity. It can be supremely helpful.

A Conclusion

One of the best way to learn, process, and remember new information is to hook it up in a relevant way to information that you already grasp very well. When it comes to that type of information, few things are better understood and retained than spaces you’ve lived in for years.

As humans, we have a very vibrant faculty of spatial memory. When you leverage that spatial memory to retain and process new information, it becomes very powerful. You can focus better, become more inquisitive, more engaged, and ultimately, smarter.

It takes some work, like any habit. But when you do it right, using a listening palace is a pretty neat trick to get more out of your conversations with others.

Did you find value in this piece? Consider subscribing to my weekly newsletter — Woolgathering. It’s one email per week, with interesting stuff to ponder, from me and from around the web.