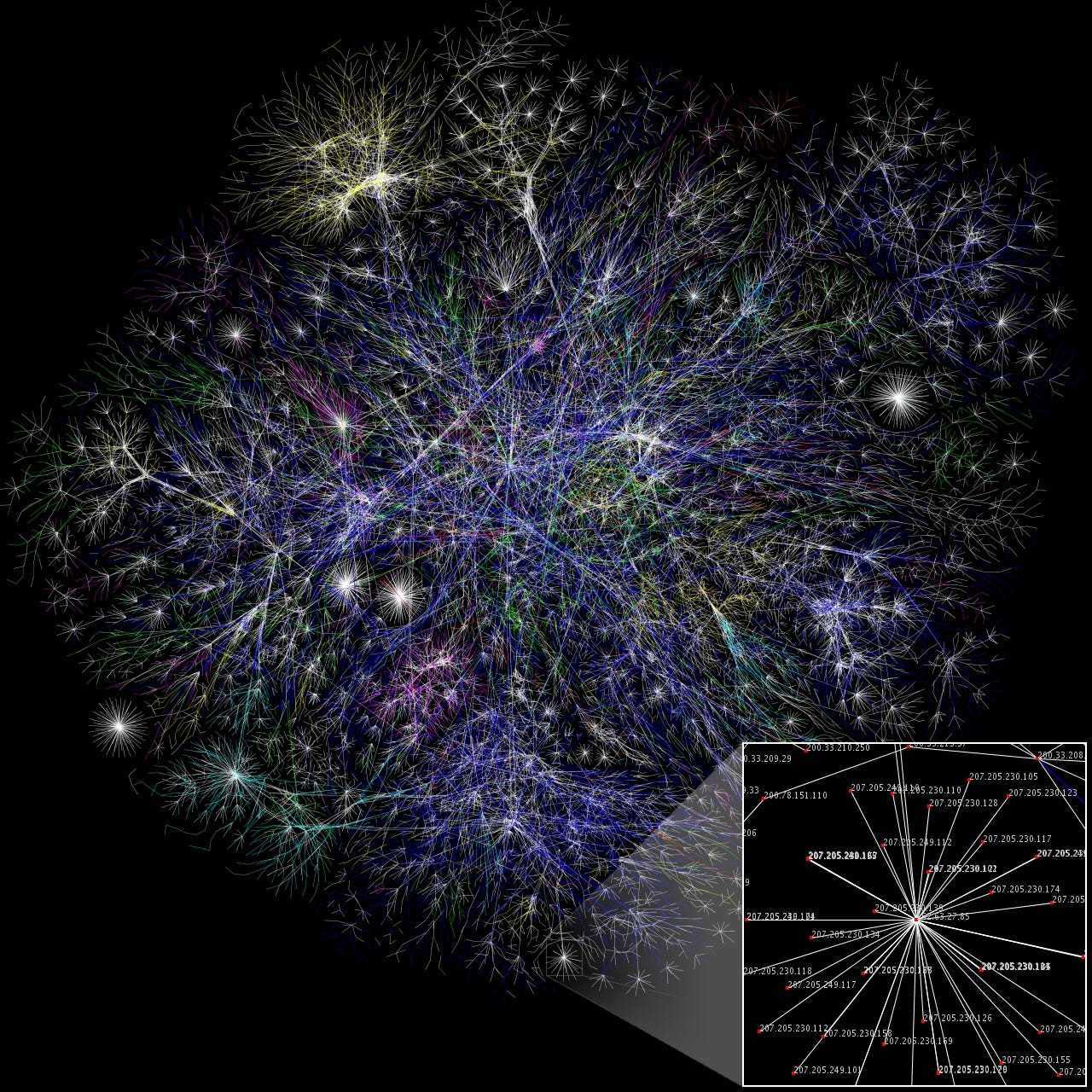

image credit: The Opte Project

What Google, Facebook, and Media Companies Must Do if They Want the Truth to Prevail

If you keep track of Twitter trends at all, you’ll likely have seen that a trending topic is the fact that Google and Facebook are taking actions to sanction what they call “fake news” outlets. On the face of it, this is good news — no matter which party or politicians you favor. The simple motive is easy to agree with: take away the source of funding for organizations that peddle false or misleading information. When thought of in that way, it’s a pretty easy sell.

But unfortunately, it just isn’t that simple. Trump and GOP supporters have reacted on Twitter to show why:

https://twitter.com/Cernovich/status/798418791575277569

Google & Facebook Take Aim at Fake News Sites…does that mean you gonna censor yourself @nytimes?#DrainTheSwamp #DC https://t.co/58zafSRl31

— Bruce Porter Jr. (@NetworksManager) November 15, 2016

https://twitter.com/deplorablejayo/status/798528947508117504https://twitter.com/allentom/status/798528846387494912https://twitter.com/Timcast/status/798528001952477184

You get the picture. While there is certainly an element of knee-jerk reactions at work here, I can appreciate the underlying worry. Information is the most valuable commodity in the developed world. It is the basis for our decisions — personal, professional, and political. As the complexity of the world increases, what information we have and how we use it becomes more and more important. The question of who controls the channels of that information, and how easy it is to access it is an important one.

Deciding on the Truth

But more than that, there is a very important two-part question:

- How it gets determined that a piece of news — or its publisher — is peddling falsehoods or misleading.

- Who makes that determination.

I don’t think that either of those questions are easy to answer. Furthermore, we must be careful who answers those questions and how. The tweets above make it clear that there is already a crowd of people that are skiddish about the established news outlets — for various reasons.

So if this push to filter and purify the real news from the fake news comes primarily through and primarily benefits the established news outlets, it does two dangerous things. First, it confirms the suspicions of those who are already skeptical of established new sites. Secondly, it works against the goal of establishing trusted news sources, because those who had distrust of them will now be left out of the conversation.

I could see that easily leading to the proliferation of all sorts of alternative news outlets with little to no semblance of fact-checking or journalistic integrity. That leaves the door wide open for impressionable audiences to swear allegiance to them as sources of information, thus literally changing the fabric of public decision-making for millions of people.

Worry About the Right People

I myself am not worried that Google and Facebook are up to anything shady, but I’m not the type of person that their news-filtering is aimed at anyway. The very people that this news-filtering exercise is supposed to help are the very people that are most likely to be harmed if this exercise is not done right.

Google and Facebook — along with the established news outlets — need to be very careful that they don’t end up alienating the very people who they are worried about being misinformed by fake news sources. Failing to do so has the potential to backfire.

I’m not sure exactly how this gets done — I’m no PR expert. But what I am sure of is that it’s very important that it’s done right, and I’m also pretty sure it involves an honest, transparent dialogue with media and establishment skeptics. That may not be very appealing to these companies, but I don’t see how they can achieve their objective without doing it.

Did you like this piece? Consider subscribing to Woolgathering — my weekly newsletter. I promise not to email you more than once per week.