How Information Bloat is Endangering our Mental Fitness, and What We Can Do About It

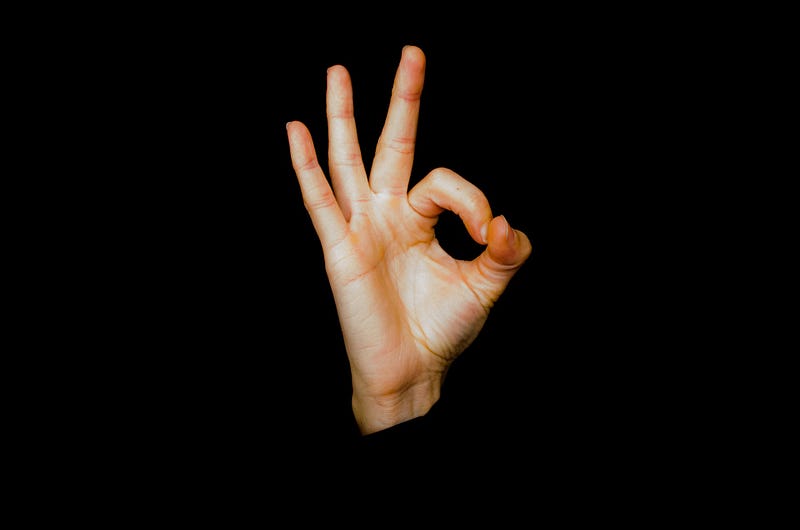

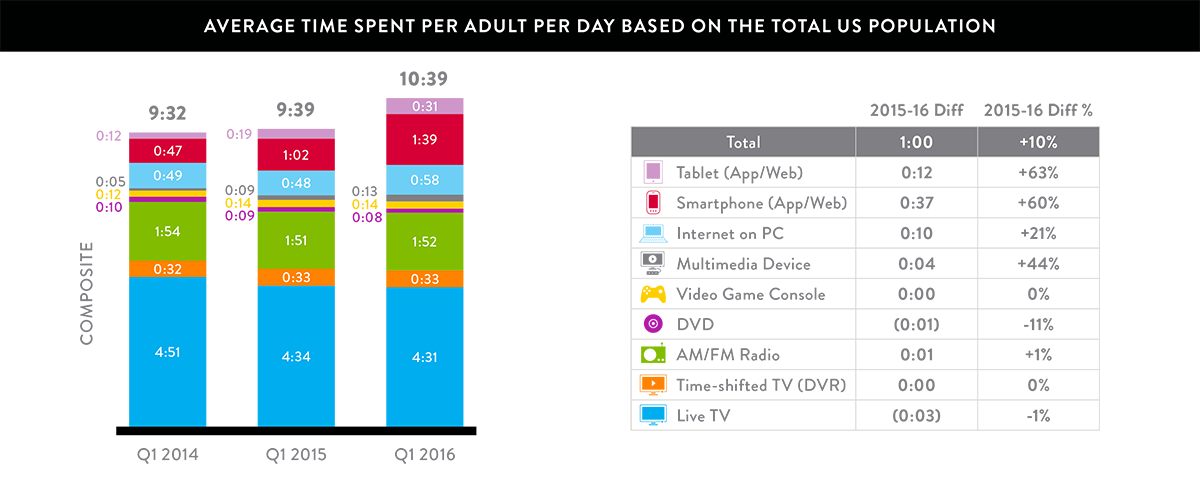

It is old news that in recent years a staggering amount of people have become obese. From 1990 to 2010, the amount of adults who are obese in the United States alone increased a staggering 57%. Other developed countries have seen a similar increase, as well.

Fig 1. Obesity rate increases over 20 years.

Among the factors cited as a major contributor to this drastic increase in obesity is the sheer volume of food that is now readily available. That is exacerbated by the decreasing nutritional quality of that food.

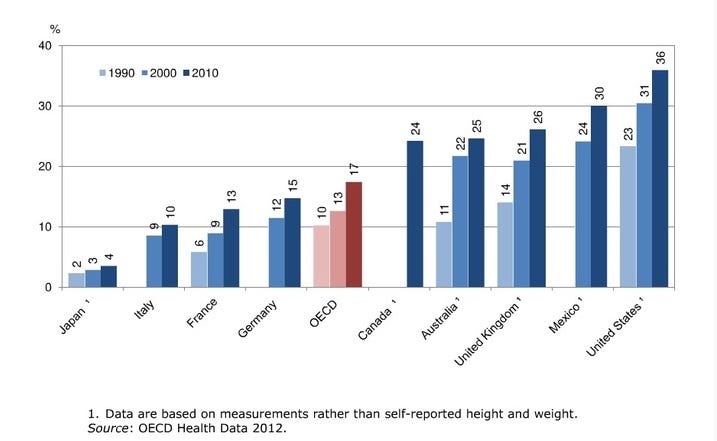

While food manufacturers feverishly increased the quantity of food they produced and marketed, the nutritional quality decreased. The more beneficial macro-nutrients a piece of food has (healthy fats and quality proteins), the more costly it is to make — and thus to buy and consume. The result is that the easiest food to make, to buy, and to eat are the worst foods for us. As a result our diets became more unhealthy over the past few decades, as we began to consume more food and food of poorer quality.

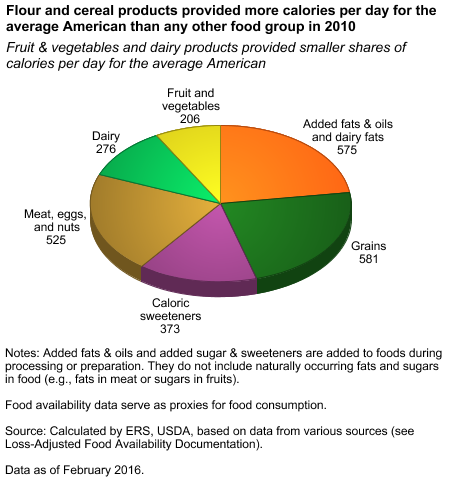

Fig. 2 — The makeup of the American diet

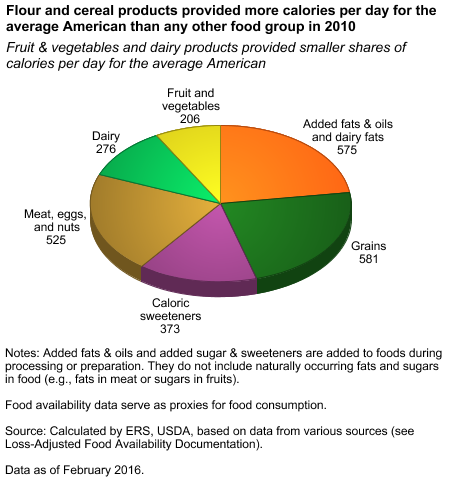

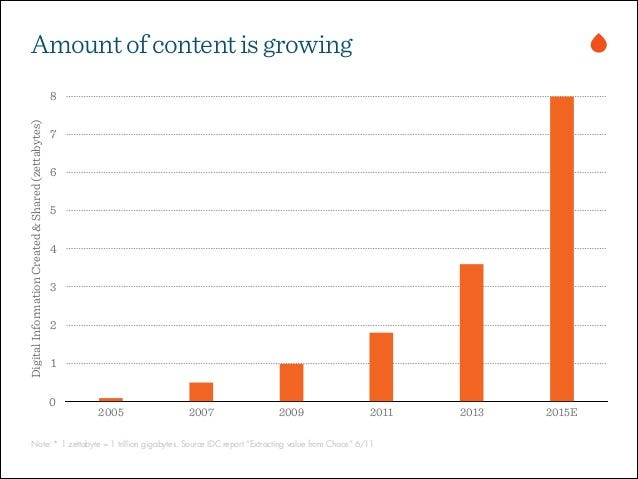

Interestingly, a similar trend to the one in food consumption has occurred in the production and consumption of information. The internet has created an environment where not only is it easier to publish and push out information than ever before, but an entire industry depends on more content being published and shared every minute of every day. And in the true style of hyper-growth capitalism, that content is exponentially growing.

Fig 3 — The Exponential growth of content

As with food, the easier it has become to publish information, the more the quantity has increased and the quality has decreased. So what do you suppose has happened to our information diet? I fear that it may be mirroring our food diet.

Information Overabundance, Cognitive Obesity

Many people have this odd opinion that there is no such thing as too much information. A veritable avalanche of businesses are built on this premise — peddling services to help keep you up to date on all the things to know, and throwing even more “things of interest” at you by the second. But why do we have this attitude toward information— that one can never have too much?

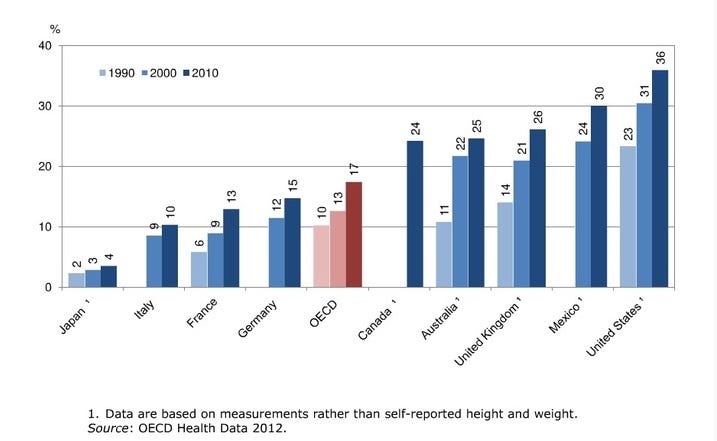

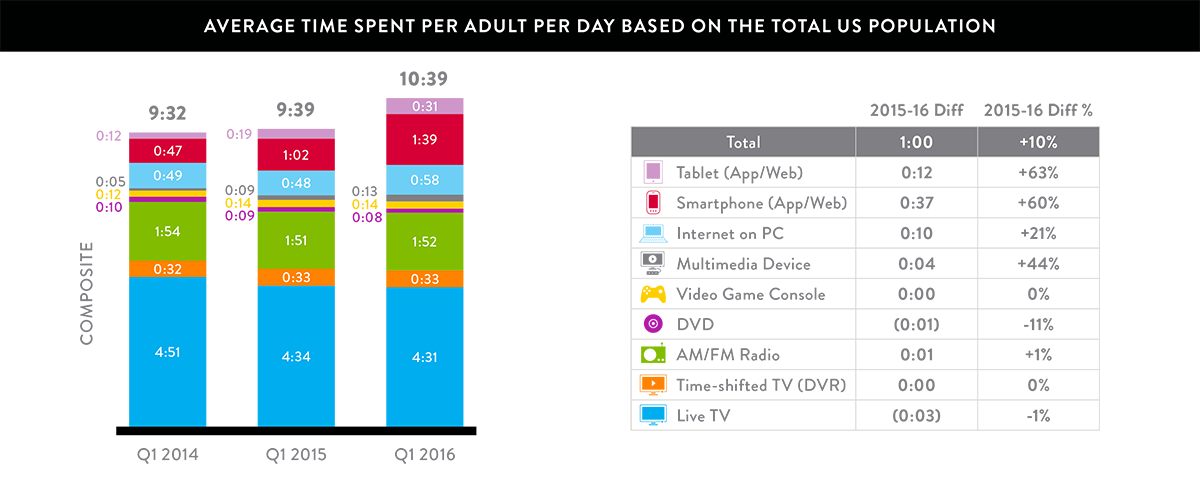

But consider how much time we spend consuming information these days. Also, consider how much more time we spend consuming it than we used to. The chart below illustrates how much more time respondents in a survey spent consuming media this year than the previous year.

Fig 4 — The time spend consuming information. credit: Nielsen

That’s right, in one year, we have increased the amount of time we spend consuming information by 10%. But how much of that additional information was quality content? See below:

Fig 5 — Trust in content. Source: http://contentsmagazine.com/articles/reconsider-the-source/

If 63% of respondents trust web content less than they did 2 years ago, imagine what that trust index could look like given the exponential increase in content (see Fig. 3) that we continue to see? It’s a grim picture, indeed.

Cognitive Load

I use the term “mental obesity”, but a better term would be excess cognitive load. A piece from the Nielsen Norman Group says it best:

Just like computers, human brains have a limited amount of processing power …When the amount of information coming in exceeds our ability to handle it, our performance suffers. We may take longer to understand information, miss important details, or even get overwhelmed and abandon the task.

Just how bad can a heavy cognitive load be?

- Several studies have associated a heavy cognitive load with an increase in errors.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

- A heavy cognitive load has also been shown to increase stereotyping, and generalization errors. [8]

In a word, a heavy cognitive load can make us mentally unfit — fatty and easily out of breath when it comes to intellectual tasks.

So, what are we as information consumers to do? The onus seems to be on us to become more intellectually fit than our predecessors, but with the glut of mass-produced informational junk-food, just how do we do that?

Perhaps we can take this food analogy to its logical conclusion. Take the advice of nutritional science, and apply it to information consumption: take smaller bites, chew for longer, and savor and digest.

Take Smaller Bites

An effective way to sift through all of the writing online is to take small bites of anything you think you might want to read. This is the equivalent of taking a small bite of something — in order to try it. Scan the entire piece for headings. Try to figure out what the piece is trying to say, and look for sentences that convey interesting or useful information.

Also look for spelling and grammar errors. Often times, if I see more than a few, I stop reading. Chances are, someone else is making the same points, but actually knows how to write well. If I’m interested in the topic, I’ll spend a few minutes finding a more well-written piece on that topic. Is that elitist? I don’t think so. I just don’t want to give my attention to someone who didn’t bother to try to effectively communicate to me. The only exception to this is personal stories and eyewitness accounts.

Attach your attention to the information. This can be anything from saving an article to your “read/review” stack, or just getting it in a psychic space that marks it as something you’re going to really look at. Don’t gum up the works with a heap of stuff you wouldn’t look at twice on a stack of paper publications.

I keep a “read/review” list in my huge Workflowy document, with links to stuff I plan to actually look over. I try to save only things that I know I will spend more than 5 minutes reading and thinking about. There’s a famous rule that governs behavior like that — stick to it.

Chew For Longer

You’ve probably heard — from time to time, and from various outlets — that chewing your food for longer is better for you (on numerous levels)? Well the same holds true for processing the information. Take and process the information that you have “bitten” off. This process should take you longer than you think it should — just like chewing food. Really swirl it around your mind for a while. Just as you’d let a really good piece of food move around your mouth to hit all the sensory parts of your tongue, so should you let all of the parts of your mind touch the information you’re now processing.

What does this translate to when it comes to information? There are a bunch of things. You can take notes. Systems like Zettelkasten or Cornell Notes can be helpful for taking notes and organizing them. Other useful systems (and related applications) abound. A really neat blog that goes deep into keeping and taking notes can be found here.

Either way, “chewing” over information longer will do two things:

- Help you to better process information, so that it becomes embedded in your body of knowledge, accessible, and thus useful (and isn’t that the goal?).

- Prevent you from consuming fluff or things that won’t end up enriching your knowledge base.

Savor and Digest

This is the part that should take the least amount of time, but only if you have a mature and effective organizational system. Think about it this way. When you’re swallowing food, you’re starting the process of having your body use the food you’ve just processed — you’re now making that food useful. When processing information — learning — it should be no different. You’re now passing along that information to that part of your mind that will store it as knowledge for you to use. Swallowing the information you’re learning involves two main things:

Verifying that you really do know it The best way to do this is by testing yourself, which I’ve found is most effectively done by having to teach or present it to someone else that doesn’t know about the subject at all. I taught philosophy at a community college for over 4 years, and I learned more about philosophy in that time than I learned in my entire time in graduate school.

It is well known that having to teach others something forces you to get a better grip on things. You may think you know something inside out, but when you have to explain it to others, you realized that you don’t. This is especially true when you have to teach things to people who don’t know much (or anything) about your subject. A favorite quote of mine, attributed to Albert Einstein, captures this truth perfectly:

“If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough.”

Organizing the information This part involves making the information readily accessible, and ready for updates, emendations, further analysis, and other reviews. It is also a way to ensure that this chunk of new knowledge finds its way into the web of your current knowledge as a connected piece. If you can’t connect what you’re now learning to what you already know, the chances of you really grabbing a hold of it go down dramatically.

The amount of “content” on the web will likely continue to increase exponentially for the next decade (or more). As this happens, it’s important to ensure that we adopt practices to guard against cognitive overload, and the stress that comes with it.