How Our Ambitions Might Just Keep us From Our Potential

From the time that I was 6 years old, I knew what I wanted to do with my life. I wanted to be an artist. I would sit down at the little table in my parents’ living room every day, break out the pencils and paper, and go to town.

Art was my passion. I had laser-focus on it all through grammar and middle school. My parents fully supported me, as well.

That passion lasted clear through high school — where I enrolled in the Art Advanced Placement curriculum. It was overwhelming. I was among 25 of my peers, who were all also passionate about art. They lived and breathed it, as I thought I did.

But they were all much better at art than me.

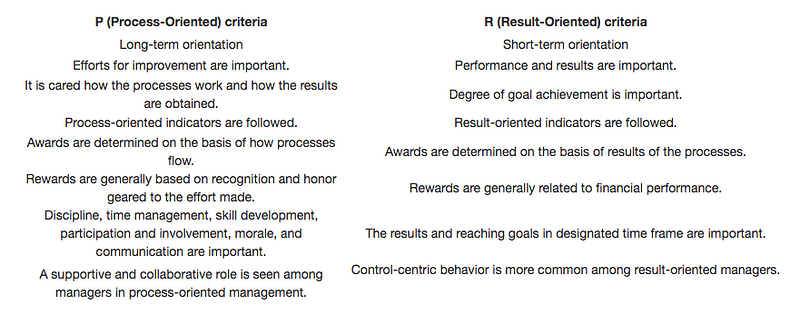

A Goal Can Be Destructive

Every day, I’d go into art class, look at what my peers where producing, compare it to what I was making, and be totally embarrassed. My teacher obviously noticed as well. When we would all put our work up to critique as a class, mine was clearly either rushed, incomplete, or showed little polish or refinement.

One day, she took me aside to talk. She started by telling me that she didn’t think I was putting in all the effort I could on my art. She was right; I wasn’t. And I knew it. But rather than scolding me for it, and encouraging me to knuckle down and get to it, she pivoted.

She said that she thought I was really good during critiques. I offered great analysis of the work, and gave useful insights about meaning and themes. She told me that I should consider writing about art, rather than expending all my energy trying to make it.

I was wrecked. All I heard was that I was failing. My classic Midwestern upbringing told me that I simply had to work harder, keep pushing, and I’d get there.

So that’s what I did, and it got me absolutely nowhere for 2 more years.

I entered college as a visual arts major, and became and even smaller fish in an even bigger pond. Nearly everyone in my classes was more talented than I was. They appeared to spend more time on their work than I did. When we displayed our work for critiques, it was the same story for me as it was in high school: my work was below the pale.

Once again, when I talked during critiques, I could go on forever talking about themes, connections, message, and technique. I like it, and felt right doing it.

Once again, I was sent a message.

A classmate of mine — who was supremely talented — commented to me that he always enjoyed when I spoke up during the critiques. He said he loved not only what I had to say, but how I said it. He asked if I ever thought to write my thoughts and turn them into something.

I laughed, shrugged off the compliment, and moved on. Again. I was failing at my goal, and told myself to just knuckle down and keep working harder.

A Failure, and a Crossroads

My sophomore year came to a close, and my “knuckling down” efforts yielded few results. I began to fall behind in completing assignments. My grades in art classes suffered.

Finally, I hit bottom. I failed my illustration class — the class that was essentially my major. I failed it hard.

I was at a crossroads. I was failing at the only goal I had ever had. Every piece of folksy advice I could remember told me to just persevere — work harder, keep dreaming, and I’d prevail. And the fact that I just couldn’t do it made me feel terrible — in so many ways.

Luckily, at that exact time when it was all falling down around me, I received the same message that I had been given twice before. I had heard the advice twice, and ignored it. This time would be different.

My roommate at the time — who was my best friend growing up — told me that he always thought I was crazy to put a fence around myself so early. His thought was that college was for finding out what your thing is, not for cementing the thing you came in with.

It’s Not About Change, It’s About Discovery

What a thought — one I hadn’t ever considered. I changed my major then and there, and never looked back.

It took another 10 years before I realized that though I had chosen a new major — Philosophy — I didn’t have to follow the career path that everyone else was following. I didn’t have to get my PhD and teach classes at a university in order to do what has always been in my heart. That wasn’t what I was after anyway. At a deeper level, I was searching for truth, for wisdom. Then job was just a neat and clean societal construct, but only one way for me to do that.

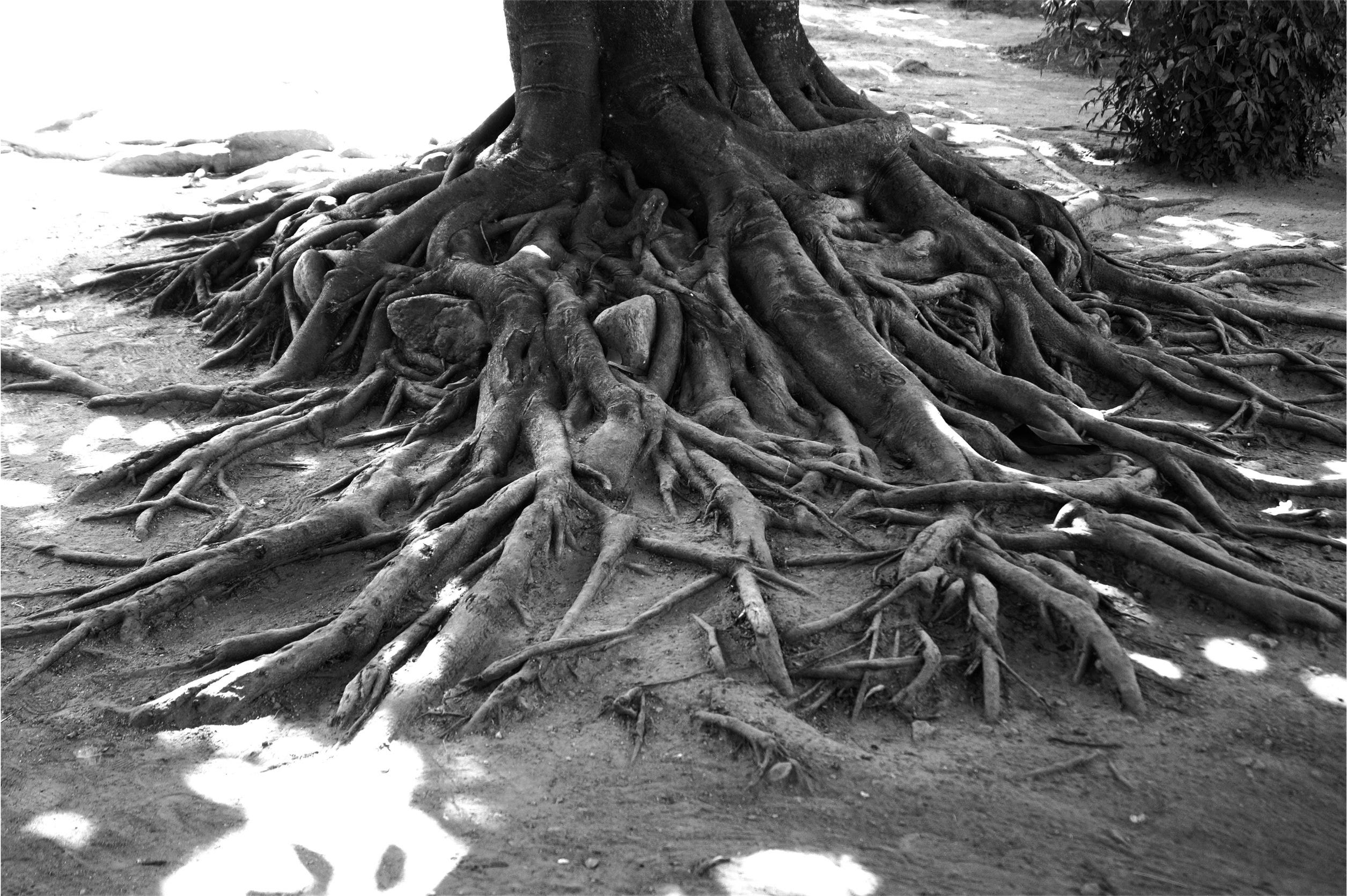

When I decided not to pursue teaching, largely because there’s an uncertain future for it, I was forced to ask even more fundamental questions about what I wanted to do. Forced into a corner — having quit on 2 goals — I finally discovered the foundation of what had been driving me the whole time: I wanted to think and write about the fundamental truths of our reality.

Any goal that I had formulated before this discovery — be it making art or reading and writing a specific subject in higher education — had merely been a constraint. I only needed to think, read, and write. That was what moved me. That should have been the goal — to continue to be moved by the need to explore the depths of our reality, not some narrow fabrication of our social norms.

Goals Should Be Fluid

My point is this: goals can actually limit us. They can keep us from reaching our full potential. The more we laser-focus on a goal, the more susceptible we are to the kind of tunnel-vision that tunes out useful advice about how we might benefit from changing direction. That advice has made all the difference in my life — twice. Luckily for me, I was able to open up to it.

But for so many others, the advice they have given themselves is to persist in chasing their goals, no matter what. The problem is that when your goals are so specific that they don’t allow you to veer off the path a bit, they become impediments.

A goal that is too rigid and too specific is little more than a self-constructed prison. It only serves to suffocate the spirit. To really find out what it is that you need to be doing, you have to look past the things that we’ve constructed to box-in people’s visions — jobs, roles, companies, etc. You have to look at what moves you at the most basic level. When you find it, there are numerous ways that you can have it manifest — in many different jobs, roles, and places. If there is a limit, it’s nothing below the sky.

Did you find this helpful? Consider subscribing to my newsletter — Woolgathering. One email per week, with stuff you can use. That’s my promise to you.