Why the Demand for Positivity and “Solutions” Is Misguided and Stifles Growth

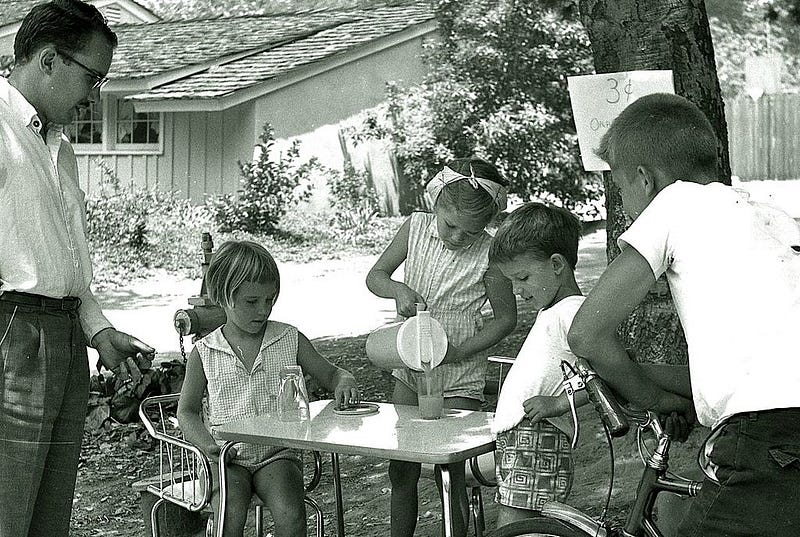

I was in a meeting once where a high-ranking executive at the company said the following (which I’m paraphrasing):

“I don’t want to hear people whining about what’s wrong at the company. Be positive and bring some positive solutions.”

At first blush, maybe this sounds okay. But I think it’s severely wrongheaded and dangerous. In fact, not only should we as leaders welcome complaints — we should encourage them. Actually, going even further, we should seek them out.

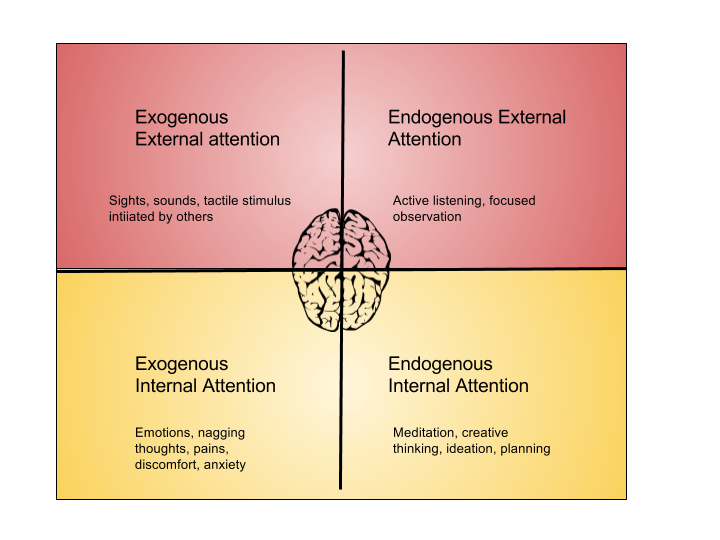

Negativity has real power, because it provides the ground from which positive growth springs. But negativity has to be handled precisely in order for it to be useful. I see 4 main directives that anyone in a leadership position should embrace when it comes to negativity:

- seek out complaints — as many as possible

- don’t create barriers to negative feedback, take them down

- handle the negativity positively

- encourage negative thinking and harness it

Seek Out Complaints — As Many as Possible

Since I began getting performance appraisals, I’ve tended to focus heavily on the areas for improvement in them. I am glad to get positive reinforcement from my managers, but I am way more interested in what I have been doing poorly at. If my manager has a suggestion about how I might improve it — great. But if not, no problem. I still want to know about it. I want to improve the things I’m not great at — if I can. I can only do that if I know what I’m not good at. And I can only know that through feedback — as much as possible.

Similarly, if you’re a leader in a company — especially if you’ve got significant skin in the game — you should be inviting all the negativity that people can muster. You should be drawing it out of them. You should savor it.

Why? Well, what is the job of a leader in an organization? What is he or she responsible for? Growth, organizational stability, direction, inspiration, etc. Well, let’s take growth as a case in point here. How does growth happen? Unless it’s by accident — which is usually reserved for very young and small companies — it happens by identifying areas of weakness and working on them.

Again, you can only get better at what you’re doing poorly at if you know what you’re doing poorly at. If you don’t ask what you’re doing poorly at, you probably won’t understand it. So ask for that feedback — no matter how negative it may seem.

Don’t Build Barriers to Negativity, Tear Them Down

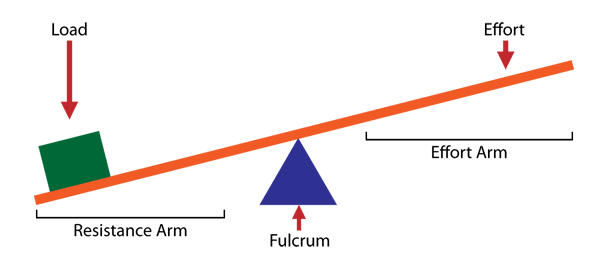

The more you ask people to come not with problems, but solutions, the more you’re stifling the free and open flow of communication. Some of the most effective and revolutionary ideas are ones that originated only partially assembled in one person’s head. They needed to be put out in the open for others to take them and work with them more — to rework and improve — to build more onto them.

Think of it this way, you hire a building inspector to point out flaws in the structure. You don’t expect them to also plan how you’re going to fix it. In fact, if they did, you’d be a bit worried that somehow they’re working with the contractor to add more into the budget. So why do we feel like when people have criticism within a company, they should also be making suggestions at how to fix it? It simply doesn’t make sense.

Separate the mental tasks of identifying problems from identifying solutions. This way, you’ll get more and a better quality of each. And that’s what you should be looking for.

Handle the Negativity Positively

You have to be able to handle negativity in a positive way. All that means is that you listen, understand, and process what you’re presented. When people complain, ask questions — clarifying questions. Don’t defend, don’t deflect, and whatever you do, don’t operate on emotions. Just be open and receptive. Even if the negative feedback is dead wrong, and you know it in your heart of hearts, two things hold true:

- Lashing out at the person giving the feedback won’t really help you get better.

- It will help you to try to understand why that person gave that negative feedback — however untrue it may be.

Problems are never just problems — they’re opportunities. Now whether you want to explore those opportunities is a choice you have to make — but they are still opportunities nonetheless. When you see things in that way, it’s a lot easier to avoid getting bogged down about having a lot of problems.

Part of being a good leader means not letting problems overwhelm you. That means not getting defensive when people throw negativity and criticism your way. Even if they aren’t trying to help you, their feedback can be valuable — just look at what they’re saying from a neutral standpoint. Does it make sense? Does it have some truth behind it? If so, it’s useful; it can inform what you pay attention to as you go about improving.

The presence of negativity in a company doesn’t make a leader good or bad; every organization has pockets of negativity. But the way a leader handles that negativity can be what separates great leaders from bad ones.

Encourage Negative Thinking

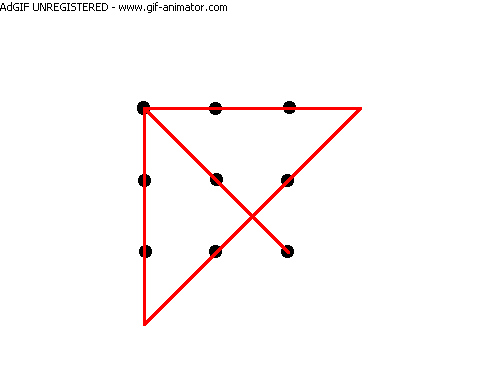

Lisa Bodell wrote a book several years ago called Kill The Company. In it, she encourages companies to do an exercise where team members sit down and think of how they would take down the company if they were its number one competitor. It has been working wonders for many different companies.

Why is it so effective? It does three important things:

- It encourages a fresh point of view for negativity — that of an outsider looking to take it down through competition

- It breeds negativity, in the form of specific weaknesses that company has

- It harnesses that negativity to help make a company better by focusing on what would defend it against being beaten in the market

Negative thinking can be extremely useful, so long as it’s received in the right way, and then harnessed for the purpose of making things better. That is the work of a great leader.

The Takeaway

There will always be negativity within a company — no matter how positive a culture one tries to create. So it is the job of a leader to handle that negativity skillfully. That means 4 things:

- seeking out negativity and complaints, with an intent to understand it

- removing barriers to complaints and problems, which often means separating them from proposed solutions

- handling the negativity in a well-meaning and strategic way

- encouraging thought about problems and complaints, with an eye toward making them work for the company’s benefit