The Power of Simple Columns, Rows, and Formulas

Photo by Esa Riutta

Almost 10 years ago, I read Getting Things Done for the first time. It showed me the importance of having a trusted system, a place for all of the things that you want to or have to do — be they personal, professional, or otherwise. That book is responsible for getting me excited about productivity tools and systems — an excitement that has been with me for my entire professional life.

Of course, systems and tools alone won’t make you more productive. I’ll be one of the first people to admit that. However, if you’ve got the basic discipline and desire to get organized and productive, a good tool can be a determining factor in keeping you on your game.

For me, that system has been GTD. It’s not perfect — no system is. But it is fundamentally sound and, when I follow it, I feel much better about how and what I’m doing, both professionally and spiritually.

Since deciding to implement it in my life, I’ve gone through several pieces of software in search of that perfect program to follow the GTD framework. I tried ToodleDo, Wunderlist, Todoist, Trello, Evernote, Buckets, Any.do, Remember the Milk, and a few more that I’ve forgotten by now. In some way, each of them missed the mark for me. They were either too rigid, too complicated, clunky, or a mixture of those shortcomings.

Recently, I stumbled into a most unlikely piece of software to implement my kind of GTD system: Google Sheets. And you know what? I really, really like it. Who would have thought a simple web-based spreadsheet program could run a totally rad implementation of GTD?

Actually, now that I think of it, that should have been one of the first apps I tried. In hindsight, it makes perfect sense. But more on that as I run down just how I use it. So without further ado: here’s how and why Google Sheets kicks some serious butt when it comes to productivity.

Why Google Sheets is so Great as a Productivity App

1. Visual Consolidation = Better Mental Processing

Clutter is a real problem — be it physical or digital — with real psychological effects. Among them are efficiency drains and lower effectiveness in processing information. Not to mention lower subjective well-being. When I look at a list of projects and it takes up a lot of space and has a lot of text and other stuff attached to it, I can feel my mind checking out. I can feel my efficiency and will to work fall away.

Google sheets is just rows and columns, and as few or as many of those as I like. So when I have 35 or so open projects at once, it’s helpful to just see those as rows on a spreadsheet, which is something I’m familiar with and which can present a lot of data in a neat and tidy format.

2. Ease of Entry, Ease of Change

A good productivity system is one that captures information easily. In order for that to happen, there needs to be few (if any) barriers to entering a project or task into the system, and few (if any) barriers to changing or adding information.

This is where spreadsheets really shine. Entering a new project or task is as easy as clicking a cell and typing in it. There are no checkboxes, options, buttons, or anything else — you just type as much or as little as you want, and there it is. If you feel like adding more information, you can add a column. You can merge cells. You can do damn near anything. As I built my particular system, I counted on being able to do just that. Productivity is very messy, it’s important to have a system that is able to accommodate that without demanding too much of the user initially. For me, a spreadsheet does that perfectly.

3. Agility

Any productivity system worth its salt needs to be agile enough to sort and filter based on changing priorities and criteria. A basic spreadsheet does just that. Google Sheets makes it pretty easy to create multiple filters based on different criteria.

Some people (especially those strictly following GTD) use contexts for each task. Each task has “@phone” or “@computer” or something similar to allow you to only look at tasks you can do based on your location or available tools. For those who use contexts in their productivity systems, the agility of filters in spreadsheets makes it that much easier to simply sort or filter based on the contexts to find the action items you need.

Google Sheets makes it easy to save custom filters with multiple criteria and sorts. You can name these filters as you wish, which will make them easier to use to find actions or projects based on what you’re looking for at a given time.

4. Simplicity and Power

Perhaps the underlying benefit of all the aforementioned ones for spreadsheets is that they are simple. And because they are simple, they are powerful. In a spreadsheet, data is put into simple order and associated with other data. That data can be something as complex as a formula that links several data points in a function, or as simple as text with no linkage or function whatsoever.

How you link all the data is up to you. And really, isn’t that how it works when you’re getting things done? You decide what gets linked up, where things go, and how they function. Shouldn’t your productivity system mirror that — at least at its most basic level? I tend to think so, hence my ending up on Google Sheets.

5. Cross-Platform Usage & The Cloud

All of the above things apply to any kind of spreadsheet — be it Microsoft Excel, LibreOffice, OpenOffice Calc, or (to a slightly lesser extent) Apple Numbers. They’re all spreadsheet programs, and work off the same basic principles of rows, columns, sheets, and formulas. But Google Sheets is entirely on the Cloud, where it works robustly and reliably.

I work on 3 different devices, with 3 different operating systems: a Windows machine for my day job, a MacBook Air at home, and my iPhone 7. Anywhere I have an internet connection, I can get on a browser and work on my GTD workbook. And on the iOS Google Drive app, I can star files for offline viewing — which I do for my GTD workbook.

How I Use It

edit: due to numerous requests, below is a link to a template to the workbook in Google Sheets:

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/15PUM1GRYXoXkuXDiGuWiF4ubWll441h8S-70ZnP25LM/edit?usp=sharing

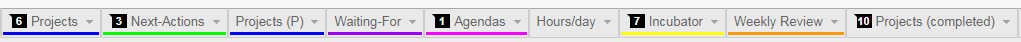

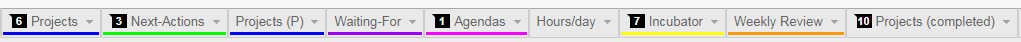

My Google Sheets workbook has 7 sheets in it — yes, 7. Each has its own purpose, and its own relationship to other tabs.

-

Projects

This is what it sounds like — a list of my projects. As David Allen defines them, a project is any outcome that requires more than 2 action steps and that can be achieved within 12 months. Because of this, I tend to have quite a few projects. As an example, I had a project to get my car’s oil changed.

-

Next Actions

A list of the actions that I could do right now for each open project, along with target dates and a rough priority number for some of them.

-

Waiting-For

A list of things that I’m waiting for from other people, along with the related project (if any), and a note about when I last spoke to them and followed up.

-

Agendas

A list of things to discuss with people at regular meetings. If I have a one-on-one with Andrea each week, I’ll put any items I want to discuss with her in here, with her name next to it. There’s also a column for the project associated with it.

-

Incubator

For those versed in GTD-speak, this is essentially a “someday/maybe” list. It’s stuff I haven’t committed to, and might like to pick up in the future. I try to review it regularly.

-

Weekly Review

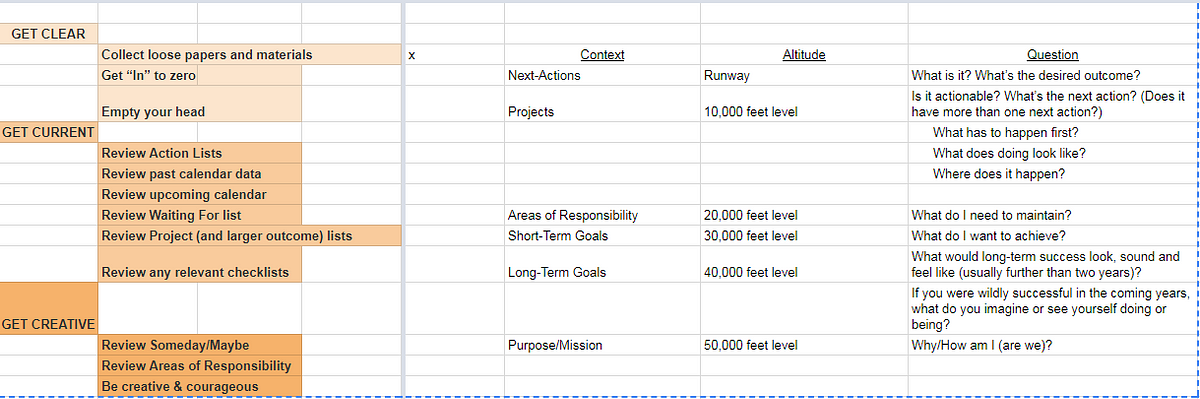

A checklist for the things that I aim to do during each weekly review. At the very least, I review each project to make sure the right next actions are in place, prioritize, create new projects, close loops, and review the incubator for new projects.

-

Projects (completed)

Again, what it sounds like. I cut and paste each project row as it’s completed, and note when it was completed. Even if I didn’t complete a project but killed it (or someone else did), or off-loaded it, I document that as well.

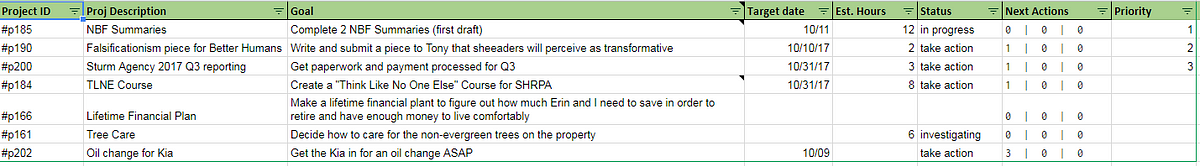

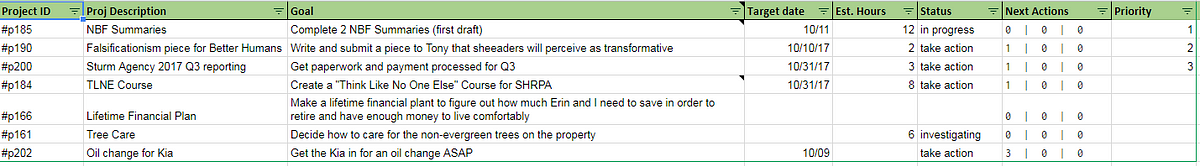

The Projects Sheet

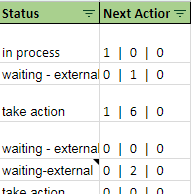

Below is a snapshot of my projects sheet. It has the same kind of columns that you’d expect a sheet to have. But it has 2 columns that really serve as the glue for this system: Project ID and Next Actions.

The Project ID is a unique identifying number that follows the scheme #pxxx (hash symbol, the letter “p”, and then a unique number). This number started with 1 when I first began tracking my projects, so that column was #p1.

I actually have a cell at the top row of the projects sheet that tells me what the next project number is. The cell has a formula that looks at my open projects, completed projects, and another tab where I keep personal projects (which are on a sheet that’s not shared). Now, I don’t have to worry about duplicate project numbers. Is that absolutely necessary? No, but it helps me make sure I don’t have duplicated project numbers floating around.

=concatenate('Next #p',max(J:J,'Projects (completed)'!J:J,'Projects (P)'!I:I)+1)

The purpose behind the project ID goes beyond just the use in Google Sheets. In fact, it’s the glue that holds my entire organizational system together. I store files and notes related to projects in various places — Workflowy, Evernote, Simplenote, Google Drive, Microsoft Outlook, and my work computer hard drive. I use the project ID to tie all those things together. I continue to impress friends and coworkers by how quickly I can locate files and information that way. Beyond that neat party trick, it helps me remember more, tie things together, and keep me more calm about being up to date on my personal projects.

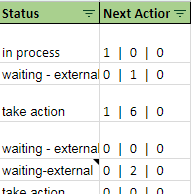

The Next Actions column tracks 3 things for each project:

- How many next actions I have listed on my “next actions” tab

- How many items related to that project I have on my “waiting for” tab

- How many items related to that project I have on my “agendas” tab

The formula is a simple “count” function that looks at those three tabs, and returns how many actions have that project ID (see how functional that project ID is?!). Why is this little column useful? Well, if you’re doing a review of your projects (which I do), you’ll want a quick way to identify which ones don’t have any activities in progress so you can ensure they get on your lists. A string of “0 | 0 | 0” tells me that there are no open actions for that project, so I had better put some in there or cancel or defer the project.

The Waiting For and Agendas Sheets

These two sheets are fairly straight-forward, and need little in the way of information. Mainly, it will be someone’s name, what I need from them, what project it’s for (named by — you guessed it — the project ID!), and notes about when I asked them for it (kind of like a log).

What determines if it’s on the “waiting for” sheet or the “agendas” one is basically the answer to the question: do I have a regular meeting with the person where I could bring this up? If the answer is “yes”, it goes on the “agendas” sheet. If the answer is “no”, it goes on the “waiting for” sheet.

The Incubator Sheet

Perhaps the most underrated — and also underutilized — idea to come from GTD is the incubator, or “someday-maybe”, list. I never quite knew how to use it until I heard an interview with David Allen where he talked about the fact that if he hasn’t done anything with a project from one weekly review to another, he puts the project in the incubator.

The idea here is simple: if you’re not engaging with a project regularly, then take it off your list of projects. It’s probably only causing clutter, and thus inducing psychological resistance to really diving into your projects and actions.

A major step in the weekly review is to look at the incubator and either move projects back into active status, keep them parked in the incubator, or delete them entirely. I try to do this as often as I can.

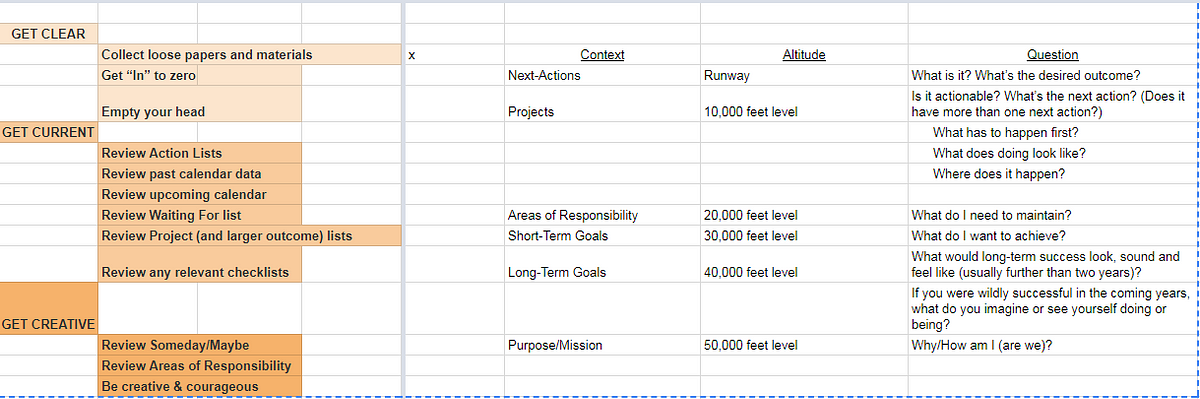

The Weekly Review Sheet

The weekly review process is critical to ensuring that your list of projects and actions are doing what they’re supposed to do — getting you the personal and professional life you want. In order to ensure that, you need to run through them all regularly (preferably weekly) in order to ensure that they are fresh.

My weekly review sheet is basically a checklist of questions and points to examine. I add and subtract things, but overall, it’s a list of triggers to remind me of projects or tasks that need to happen. It also serves to ensure that my current projects and tasks apply to my goals. Below is a snapshot of one section of my weekly review sheet.

The Projects (Completed) Sheet

I have found myself on more than one occasion asking what the outcome of a certain project was. Sometimes even when I know what the outcome was — for example, that I abandoned it — I find it useful to know when I made that decision and why I did.

So now, I keep a sheet where I cut and paste projects that are done or killed (i.e. they’re not on the projects or incubator sheets). I keep a column where I explain the outcome, like when it was finished and when I sent the finalized signed document. Perhaps this is too much for some people, but I have found it quite useful.

Using the Workbook

I begin each day by opening my GTD sheet. I look at the action items I didn’t complete yesterday and move them to today or further out. I look at my projects list to prompt me for new action items to do today. As I check my email, I’ll mark off any items that I was waiting for that have been completed. I’ll also update notes on project statuses and move dates in or out based on new information. As needed, I’ll update agendas for certain projects as well, or delete agenda items when I no longer need to address things in standing meetings.

I do this on various devices, too. It’s not unusual to see me at home with all 3 devices open and looking at my GTD sheet and email. Whenever I’m on a plane, I make sure to update my GTD sheet and then use it on my iPhone to look at projects while I type notes or complete tasks on my laptop. I try to be as cross-platform with it as possible. It’s a big reason why I chose it in the first place.

Features in Google Sheets

Notes

I use Notes for several things. One is to start listing all the next actions for a given project that I can think of. Then, I can literally copy them from the note, and paste them into my next actions list with a date to target for completion.

I also use Notes for just what they sound like — to be quick notes. For my projects tab, I’ll put notes on the status of a project to log some major milestones or relevant status information.

You can use Notes in a variety of ways, and it’s as easy as right-clicking on a cell and selecting “insert a note”. It’s even easier on the iOS app, where it’s available upon selecting a cell.

Comments

Comments are pretty cool, but I’m still working out the best use for them. They autoformat hyperlinks, which Notes do not do. That has been useful for me on a few occasions. Also, the amount of comments in a sheet is shown in the tab as a parenthetical value. So theoretically, you could reserve comments for items where it would be important to see how many comments are on each sheet. For me, this is a work in progress.

Much like the Notes feature, you simply right-click on a cell and click “insert comment”. And the great thing about comments is that they allow for collaboration. Anyone with access to your sheet can comment on cells, and comment on your comments — like a conversation. Each commenter’s name is noted (or anonymous user designator) to allow for easier tracking.

My Humble Suggestion

I’ve used so many different task and project management programs for personal productivity that I have become a bit disillusioned by most of them. I have found that a spreadsheet allows me to work in a very agile but intuitive and organized way. Plus, it’s easily cross-platform.

For those either just beginning with personal productivity systems, or those who are looking for a fresh new tool to use, look no further than spreadsheets. They’re not just for number-crunchers!

The Better Humans publication is a part of a network of personal development tools. For daily inspiration and insight, subscribe to our newsletter, and for your most important goals, find a personal coach.