credit: Oleg Laptev on Unsplash

And 5 Ways to be more influential

In some way shape or form, we all want to be influential. Whether our desired sphere of influence is merely our family and friends, or an entire market — to be able to influence is a valuable skill. But for as valuable as it is, it’s also highly misunderstood.

You see, our idea of influence is out of whack. We have too narrow a definition of what influence is, and of how it works. Because of that, we have no way to get better at becoming more influential. As a result, we often find ourselves at a loss as to how to improve our ability to influence.

My mission in this piece of writing is twofold:

- To correct the way that we think about influence, revealing a more nuanced and useful concept of it.

- To provide a few sensible and effective habits to help in becoming more influential.

How to Think Differently About Influence

Most of us operate with a much too narrow idea of what influence is, and how to exercise it. We tend to think of influence as the power to get others to think or act in the way we would like them to. This is only a small part of what real influence is. But because we have this narrow view of the concept, we often fail to recognize influence when it’s happening.

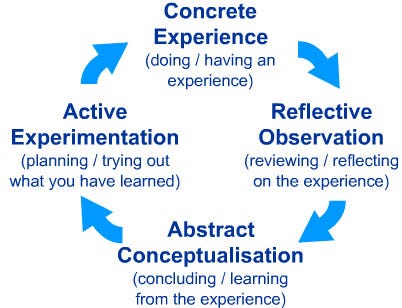

Part of the problem is a failure to think about influence as either an indirect and long-term phenomenon. Influence does not have to be direct — that is, it does not have to, and often isn’t directly traceable to one person. That is, after all, the power of compounding interest; a few small, nondescript actions now snowball naturally into a big impact down the road. In many cases, those initial small actions are barely noticeable from the viewpoint of large change over time.

Also, it is entirely possible that you can get someone to believe something once or twice based on your particular dynamic with them. But if at any point you give them reason not to trust you, the power of influence is severely diminished. So while there was once influence in the short term, it becomes unsustainable for any significant period of time. And in many cases, the more someone is aware of influence, the power of said influence becomes weaker.

Another problem with our view of influence is our tendency to think about it as asymmetric. We tend to think that influence is an act of one person asserting their will over another. I believe X and you get me to believe Y, or I’m not sure what I believe, and you convince me of Y. You’ve influenced me. But that’s much too simple a way to think about influence.

The martial art of Aikido is practiced by millions of people around the world, including those in law enforcement and the military. What makes Aikido a go-to martial art is its counter intuitive approach to conflicts. Aikido is all about using your opponent’s force against them. Rather than trying to counter their roundhouse kick with an equally forceful block or counter-attack, Aikido encourages you to allow your opponent to forcefully attack, but then use that force against them.

In a way, Aikido is actually more about allowing your opponent and their momentum to mold you, until you are molded into a shape that allows them to defeat themselves. When you realize that force can be met with flexibility, and that momentum can be leveraged, you gain a great deal of power. I think the problem is that we don’t recognize power when it doesn’t fit into our standard model. The same is true for influence.

Influence can be very similar to fighting in martial arts. There is force behind what people already think or feel. To attempt to counter that force with your own often results in the other party becoming rigid and on guard. It also results in you having wasted your energy, and losing most — if not all — of the other party’s willingness to listen.

How to Be More Influential

Okay, so influence is not asymmetrical, and it’s not a direct or short-term phenomenon. But how does that affect how we should work to become more influential? Quite simply, it should make influence a hell of a lot easier. Since influence is not asymmetrical, you can leverage that to change your approach to influencing.

Here, it helps to think like the Aikido practitioner; go with the momentum, and use it.

The simplest way to be more influential is to be more influence-able. You read that right. If you want to have more influence over more people, you need to be willing to be influenced more yourself, and make it clear to others.

Influence isn’t about making others think and act as you’d like them to. Rather, influence is the ability to align thoughts and realities — whether that happens by changing your thoughts or others’, or by changing the realities.

Your Influence = how influence-able you are X the extent of your network

So how do you do that? Here are a few suggestions to help.

-

Listen with the intent to understand.

Often times, those who are trying to influence listen only in order to talk more, or barely listen at all. But that kind of listening doesn’t allow you to be influenced at all. Any kind of receptivity that others have to you will be short-lived or quite small. If you can listen with an intent to draw a vivid picture of where the other person is coming from — how they see the world — you can establish a point at which to use their thoughts and feelings, their momentum, in order to have greater influence. -

Give without expectation.

There is a phenomenon in the psychological literature called the principle of reciprocity. It basically says that (all other things being equal) when you do something for someone, they tend to feel an obligation to do something for you. It’s not a law of nature, mind you, but it points to a somewhat reliable force that underlies social interactions. You give some, and generally people feel the need to give back. If you give and it’s clear that you don’t expect anything in return, people tend to take notice. It builds the kind of reputation that people give more credence to. -

Be sincere and understated.

The concept of authenticity is thrown around quite a bit these days, and I can see why: people respond well to people who are authentic. But I have had a lot of negative experience with people claiming to be “authentic”. Such people have gone through great pains to project a more idealized and flamboyant version of themselves (usually as they’d like to be, but not as they are). So I am not quite sure what authentic means anymore.

I prefer to use the term “sincere” instead. Sincerity is simply presenting yourself in a humble, respectful, and truthful way. It is to present your beliefs, habits, and accomplishments in a way that could never come off as bragging, and which indicates true humility. We’ve almost all met someone like this, and if we’re not extremely self-absorbed, we’ve likely been moved by such sincerity. Sincere people are influential; maybe not in the short-run, but most definitely in the long-run.

And here’s a hint: if someone is actually being sincere, they won’t have to tell you they’re sincere. -

Be ready, willing, and able to change your mind.

There is nothing more aggravating than someone who simply won’t change their mind. At best, they come off as ignorant, and at worst, they come off as disrespectful. Neither trait allows for any sustained influence. If you are ready, willing, and able to change your mind when presented with new information that conflicts with your ideas, people will listen when you present your ideas. They will know that said ideas are well thought-out, and have stood the test of scrutiny. -

Don’t get attached to desired outcomes.

Here’s a news flash: plan as you might, things rarely turn out as you either planned or hoped. That being the case, it will always serve you well to have less of an emotional investment in particular outcomes. There are times where we become so attached to a goal — and stay so focused on steering things toward it — that we fail to see the opportunities that present themselves when things go off the rails a bit. When the planned path diverges a bit, it can be a chance to re-evaluate, and realize new potential gains. That spirit is contagious, and can get a lot of people wanting to work with you. The opposite — tunnel vision and exclusion of spontaneity — can push many people away.

The Short Principle of Influence

Influence is more nuanced than we think. It’s not about power in any conventional sense of that word. It’s not about having an audience per se. It’s also not about persuasion — at least not as much as we tend to think.

You can be influential without even telling others what to do. In fact, it’s more likely that you will be if you don’t. Simply being the type of person that others enjoy working with, and that people respect intensely makes it easier to get things done.

There really is no shortcut to this. It needs to be cultivated over time. But the good news is, you can start right now, and it doesn’t matter how many people follow you on Instagram.