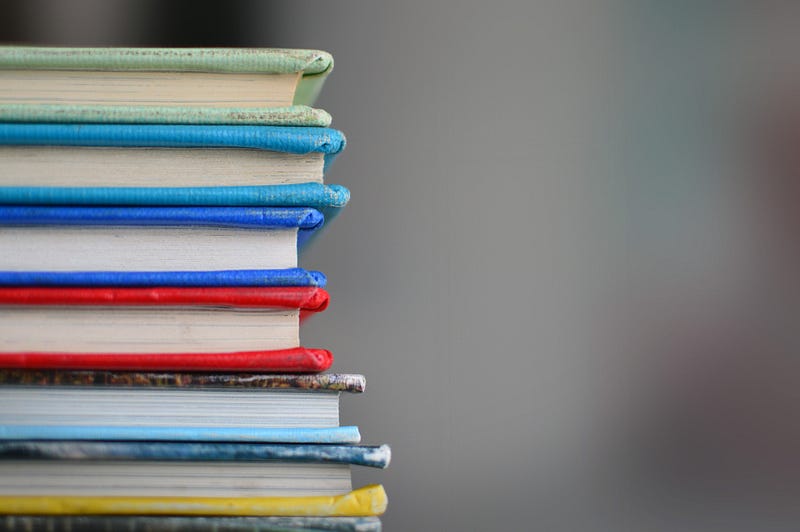

These books changed the way I think, and because of that, I go back to them time and again.

Photo by Kimberly Farmer on Unsplash

There is something special about books. Whether they’re paper books, e-books, or even audiobooks — the book has power that few other pieces of media do.

Perhaps it’s the self-contained nature of the book that makes it so potentially powerful. It has clear boundaries that separate it from the swirling sea of information outside its covers. It seems to force us to take shelter in it — shelter from all the other information flying at us.

Here’s my list of 10 books that changed the way I think, and thus changed my life forever.

Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity

By David Allen

I found this book right as I began my first office job out of grad school. I was a point in my life where I needed to decide what my career path was going to be. This book gave me a way of looking at my work and my life that pushed me to go well beyond “I just need to finish my work and go home”. If you let it, this book will change your approach to damn near everything. It provides a set of tools to achieve and maintain peace of mind. No joke.

Allen’s approach goes beyond just completing tasks. It’s about getting your mind clear of all the open loops that are weighing it down — and trust me, there are a lot more than you think. It’s as much a system for living as it is for working. It’s practical, well-written, and insightful.

The Dhammapada

Translation by Eknath Easwaran

The Dahammapada is one small book of the many books of the Buddhist canon. It is considered by many to be the best single source to capture the essence of Buddhism — regardless of the particular flavor of Buddhism that one may prefer. It’s short, divided into quickly-read chapters of verse, and they make a pocket version (which is super-handy).

It contains all sorts of tidbits of practical wisdom for living. At the center of it is advice on how to live a life with less disappointment, frustration, anger, and worry. It emphasizes just how much your own thoughts, feelings, and emotions can influence your days, and how your life goes. Whatever you’re going through, it’s you going through it, and even if you get help from someone else, your mind needs to be in the right place to really move forward. The Dhammapada provides some great advice on how to make that happen.

When Breath Becomes Air

By Paul Kalanithi, MD

There’s nothing to help you appreciate the life you have quite like the first-person account of what it’s like to die way too young. This book is a story written by a bright, young doctor who is given a death sentence in his early thirties, and must come to deal with it through writing.

Dr. Paul Kalanithi was a neurosurgeon at Stanford, but was steeped in philosophy, classics, religious studies, art, etc. This book is a memoir about his life as a thinker, a doctor, a husband, and a new father, up until his death at a young age from cancer. It’s a really great read — filled with profound thoughts on the bigger aspects of life. But it’s also filled with warm accounts of lessons learned by actually being there as people took their last breaths.

While Kalanithi’s own account of his journey toward death is moving, my usually stone cold heart was nearly melted by the epilogue. In it, his wife, Lucy, picks up where Paul left off — when he became too ill to even write. She lays out in heart-breaking detail his last days and moments of life. It is gripping, but told in such a way that you really feel what it must be like to be in your final moments of life. It’s a fantastic book.

The Tao Te Ching

by Lao Tzu (various translations exist)

I go back to this book again and again, and I find something new and helpful every time I do. It’s a short book of just over 80 small chapters, but each of them leaves you with something to chew on, and a different way to approach your day. I often make a habit of reading one chapter per day in the morning, just to give my day a jump start of fresh thinking.

Translations of this work can vary greatly, due in large part because of the language gap between old Chinese and modern English. But in a way, that’s part of what makes this book so good. You can catch a glimpse of what the book is hinting at — even if the wording is quite different from translation to translation. I recommend the translation by Thomas Cleary, but there are plenty of good ones out there.

Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less

By Greg McKeown

I first read this book as I began to give up the ghost on becoming an academic, and it helped me come to grips with my new career path. I credit it with helping to slow my roll, and focus on sifting through all the noise to find the signal. I am sure that it will do the same for anyone else who chooses to read it.

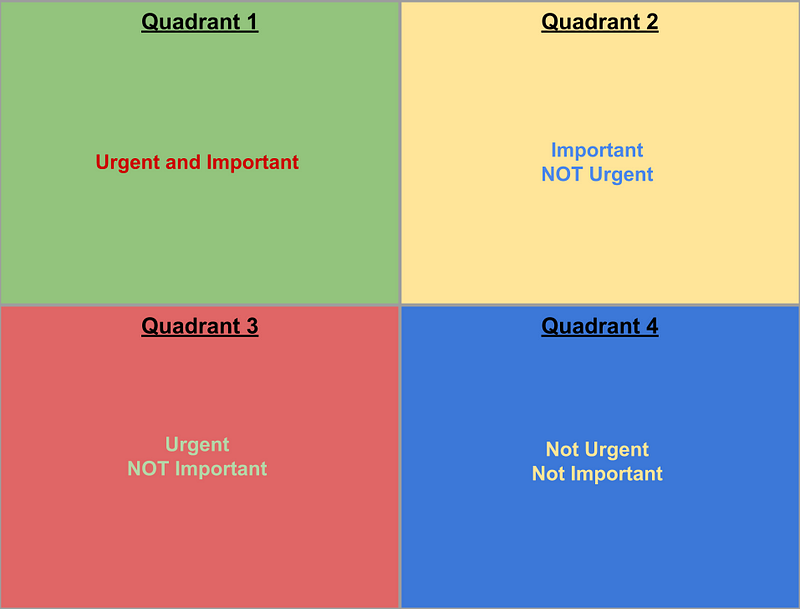

McKeown is masterful and helping the reader focus on a way of thinking that cuts through BS and false urgency. He lays out some great practices for getting you to do important work that adds value to your life and your world. It’s a great one to keep on the bookshelf and read every once in a while.

Recently, McKeown started a podcast of the same name, and it’s great. He interviews people from the famous to those of us just trying to get by, and does a great job digging into deep ideas.

Autobiography of Malcolm X

By Malcolm X and Alex Haley

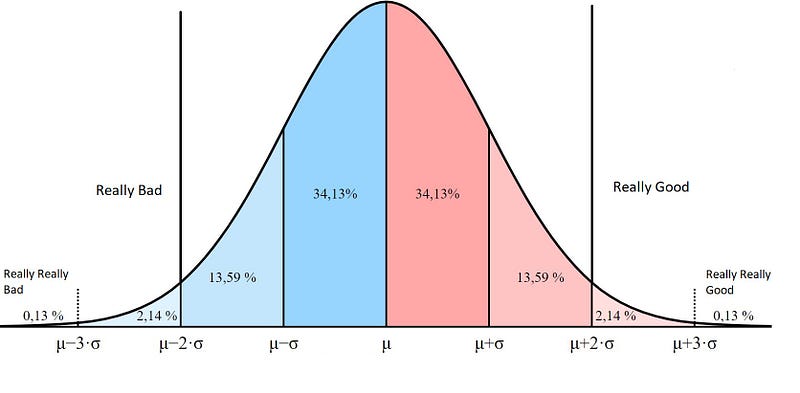

People often think of Malcolm X as a kind of militant and brash activist — which at one time, he was. But what many don’t realize is that he was on a grand intellectual and spiritual journey, which this book does a great job of documenting. Malcolm narrated it to Alex Haley not long before his assassination in 1965.

One of the traits that I have found to be most admirable in public figures is the willingness to evolve right in front of the eyes of the public. To really do this demands a lot of other admirable traits, like open-mindedness, humility, intellectual curiosity, and honesty.

Malcolm’s story is a prime example of the manifestation of all of these traits. His tale is one of imperfection, which he fully embraced and utilized to push further toward discovering the truth, and toward justice. He takes wrong turns along the way, and is never afraid to change course — even if the costs may be substantial (which they were). If nothing else, this is just a really good read about an important, and kind of (sadly) misunderstood historical figure.

The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People

By Stephen R. Covey

This book is considered a classic by many in the broader business world for a reason: it’s packed with really good advice. The 7 habits are highly intuitive, and if followed, it’s easy to see how they can make one a very effective and successful person. The great thing about it, though is it’s not like some other books that are lauded by many a business douche. It ties together success in work and life, and defines them in a way that isn’t about squeezing 10x out of everything and traveling to various destinations. Covey deals with the meat and potatoes of life — the relationships we build and maintain. Those are difficult work at times, and Covey has good advice on how to do that work.

Meditations On First Philosophy

by René Descartes

This book got me hooked on philosophy — a drug I’ll never be able to kick. My very first philosophy course largely revolved around this book in particular, and philosophical skepticism in general — a topic I still adore.

The book is accessible in a way that many (most?) philosophy texts tend not to be. It’s funny, has a good flow, but most importantly, it gets you thinking differently.

Descartes was the first widely-read author of his time to get people to take doubt and skepticism seriously. He was writing at a time when so much was taken for granted. In this book, he forces us to stop and consider how much of what we think we know could easily be wrong.

This is a great read to get you in a mode of reconsidering received wisdom, or anyone hungry for a different way of looking at things. Consider it as planting the seeds of innovation and creativity.

Not Always So

By Shunryu Suzuki

I read this book at the behest of one of my mentors — Dr. Grant Olson — who helped point me on my way with regards to learning the ins and outs of Buddhism. I am by no means a pious Buddhist — hell, I’m lucky to even meditate a few times per year. However, this book (and a few others by the same author) is so rich with prescriptions for how to think about life, death, emotions, pain, and all that thorny stuff of life — it has something for anyone just looking to re-frame their view of reality.

Suzuki had a way of simply and concretely offering up arresting insights into our mental lives. I’ve read this book many times, and lent it out to a few people. I continue to go back to it regularly because it is so easily digestible and refreshing.

The Miracle Club

By Mitch Horowitz

Every once in a while, you should read a book that stretches your worldview a bit. I’m talking about the kind of book that you might initially scoff at because you just “don’t believe in that stuff”. This book is a good one to choose for that purpose.

Horowitz balances critical exploration of new age thinking with an argument that, despite some of its followers unbelievable claims, it’s still worth our attention. He explains many of the new age movements out there, and offers up some of the practices that he has adopted over the years from new age thought. The result is a balanced book about a topic that tends to be neglected by the more analytical self-improvement crowd.

I’ll always hold science in high regard, but this book gave me a new perspective on the systems of thinking (many of them ancient) that have existed outside of science for a long time. You can’t call yourself open-minded if you haven’t ventured outside of the accepted ways of thinking. Picking up this book is a great way to do that.