If you have 3 minutes at the end of the day, you can do this — and it will change the way you approach each day.

Photo by Daria Shevtsova on Unsplash

Here’s a question for you: what were you doing at this time 4 years ago? Unless a huge life-altering event happened to you at that time, you might have trouble answering the question. If you did have trouble, it’s likely because you don’t keep a journal.

By now, you’re probably familiar with at least some of the benefits of journaling regularly, so I won’t recount them here. But I will discuss a problem that many of us face regarding journaling: it seems to daunting to do regularly. So we don’t end up doing it, and thus don’t reap the benefits.

Well, I love simple and elegant solutions to persistent problems. So here’s a good one for you.

The problem

You don’t have time to journal. Or maybe the prospect of sitting down to write out what happened during the day makes you want to curl up in the fetal position on the floor. I feel your pain.

Heck, I’m a writer, but I still struggle with the idea of sitting down to journal. But we’re all aware by now of the documented benefits of journaling, right? It helps you get more focused on what’s important. It helps you better process what happened during the day. It makes you a more present person, and prevents weeks, months, and years from flying by with you being unable to remember what that time meant to you.

So what do you do?

The Solution

The 3 x 3 journal. Take no more than 3 minutes at the end of your day, and answer these 3 questions. Take no more than 1 minute on each.

- What did I get done today?

- What should I have done, but didn’t?

- What will I do differently tomorrow?

It’s dead simple — almost too simple. But that’s the point.

When done correctly, these three questions help you establish 2 effective habits. First, they get you in the habit of reviewing your day in terms of what you accomplished (praise and recognition for yourself), and what you are motivated to change (the basis of personal growth).

Secondly, reflecting in this way each night trains your mind to approach your day more proactively. Because you know that at night, you’ll be recording what you did, as well as what you’d have done differently, you’ll tend to be more motivated to accomplish important things. There is a bit of shame in writing “I didn’t accomplish anything,” or in listing things that are not in line with your priorities.

How to Do it

There will be the temptation to complicate this process, but it’s important to keep it simple. List one or two things under each question. Write less than you feel like writing. That will keep it a habit for longer. One minute per question may not seem like a lot, but in this context, it is—as long as it’s a quiet minute, where you’re not distracted by other things.

An important note here is that your answers to each question should be both specific and realistic — specifically your answers to the second two questions. Don’t come at this from a place of how you see your self ideally years from now. Don’t come at this from an angle of thinking you can be perfect tomorrow. Be realistic with yourself.

What did you get done today?

You can list as many things as you want, but the best way to answer this question is to think in terms of priorities and progress toward goals. This should happen a bit naturally, as having to write things out tends to discourage listing things you’re not proud of having gotten done.

You can look back at a to-do list that you used, but that’s wholly unnecessary, and probably a bit distracting. The point of this question is for you to look back during a time when you’re not in the thick of work and activity (i.e. about to go to bed), and reflect back on your day.

What Should You Have Done, But Didn’t?

As you list out what you did get done, you’ll probably come up with something you know you should have done, but didn’t. We all have those things, as most of the time, we know we could have done just a little more. List that here.

But don’t get carried away. Limit your answer to this question to one thing. The point isn’t to beat yourself up about what you didn’t do. The point is to record one area for improvement. Any more than that is just beating yourself up.

It’s also important to be realistic. Whatever you list here should be something you could have realistically done — given your constraints during the day. The underlying question here is simply how you could have done just a little better—emphasis on little.

What Will You Do Differently Tomorrow?

Your answer to this question will likely flow right out of your answer to the previous question, but not necessarily. In some cases, what you will do differently tomorrow has a lot to do with what you didn’t do today. But in some cases, it’s actually what you did do today that establishes what you want to avoid tomorrow.

This question allows you to play back the tape from today’s game, if you will. You can think about how things played out, and search for times where you felt like you tripped up a bit, made the wrong decision, or acted thoughtlessly. Think about habits you’re working on, and if you didn’t stick to them. Did you stray outside your diet? Did you not work out? Or did you say something to someone that you know was ill-advised or flat-out wrong?

This question gives you the opportunity to take what you uncovered during the first two questions, and turn it into a positive commitment. You will do this tomorrow. You will make this change. And so on.

Again, be sure to be both specific and realistic here. Writing “I will be a better partner tomorrow” or “I will be more grateful” is a cop-out. That’s not an action you can take tomorrow, it’s the result of many days’ worth of action. Limit your replies to concrete actions you can take tomorrow, which will make your answer to the first question tomorrow one you’re proud to write.

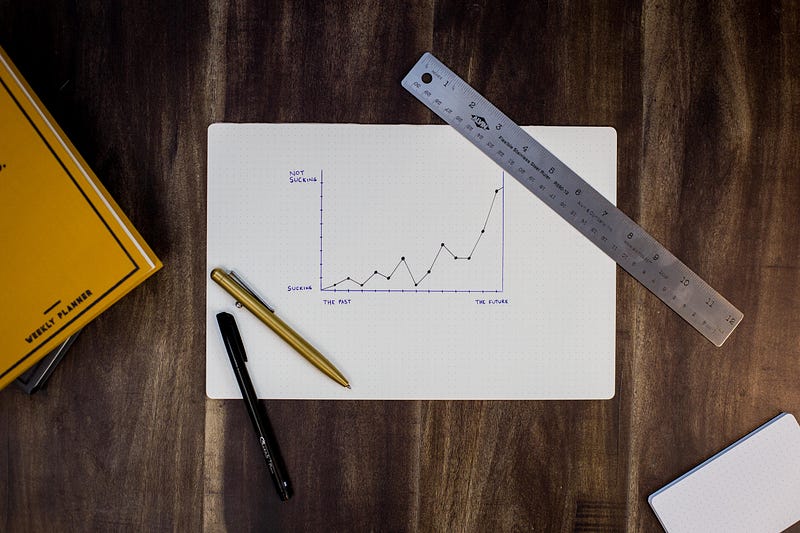

Learn to Make Yourself Proud

A big part of this exercise is learning how to be proud of yourself. It’s not about being boastfully proud and cocky. But rather, it’s about providing a way to recognize what you did, as well as set up a clear and specific route for getting better tomorrow.

This exercise should make you feel good, and give you a bit more of a purpose throughout the day. You want to be able to write answers tonight that you’re proud of. So when your’e making decisions throughout the day, think about the fact that you’ll have to write about them tonight, and work to make your answers ones you’ll be proud of!