Photo by Ben Sweet on Unsplash

A More Meaningful and Holistic Approach to Lifelong Learning

We spend all day being bombarded by information. We take in what we can, leave what we can’t, and we keep moving. But as the sheer amount of available information grows, and most of our jobs require us to have more of it, we tend to have less and less time to process it. And when we do have time to process the mounds of information we take in, it’s increasingly unlikely that we’ll process it in any meaningful way.

What we lose is insight — which can be defined in a few ways:

- an instance of apprehending the true nature of a thing, especially through intuitive understanding

- penetrating mental vision or discernment; faculty of seeing into inner character or underlying truth.

- an understanding of relationships that sheds light on or helps solve a problem.

Insight is a few steps above mere knowledge. It’s more than simply knowing the what— it’s knowing the why. It’s more than grasping facts about the surface levels of topics, it’s understanding the significance and meaning of things, the forces at work inside, under, and between. When you have insight, you can see connections and relationships that others might miss. It’s the kind of thing that an algorithm can’t quite capture.

Like any other beneficial quality, insight comes through habitual practice; you have to set aside time to cultivating it. The way to do that is through a regular practice of reflection.

What is Reflection?

Reflection is a process , but it is also a mindset — a psychological disposition. But unlike critical thinking or creative thinking, it is not directed at gathering information or solving a problem. Rather, it is about establishing meaning and connections at a deeper level — often between disparate and seemingly unrelated ideas and events — which tends to more deeply embed new pieces of information in your psyche.

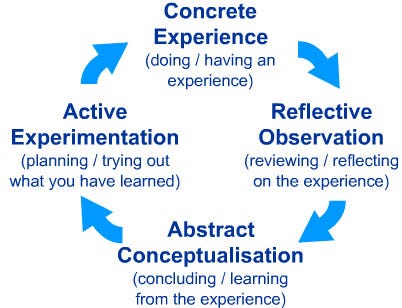

In the 1980s, educational theorist David Kolb published work on how reflection is an essential part of a robust learning process. Rather than just gathering facts and immediately turning them into knowledge, we need to put them through a 4-part cycle in order to make the most of the information we have.

The cycle consists of an input (experience, facts, or data of any kind), a process of reflection on the input, abstract conceptualization, followed by active experimentation, which creates an output of insight and new concrete experience — thus beginning the cycle again.

c/o simplepsychology.org

The steps in this cycle rarely happen separately from each other. Rather, they tend to happen as new information is being absorbed and processed. That means that to get better at using this cycle for learning, you have to condition your mind to go through these steps in the cycle as part of any new piece of learning. But many of us simply don’t do that.

Any time we encounter new facts or experiences, we at a minimum engage in phase 1 — that is, we gather new data. Some people tend to think that just gathering that data and experience — and perhaps a brief rehashing of it — is enough to get smarter. To an extent, just being a collector of facts and experience can serve to make you smarter — but such superficial collecting isn’t the kind of deep learning that truly makes the most of the facts and experience gathered. And it definitely doesn’t stoke the fires of curiosity that are necessary in being an effective learner. That’s where reflection comes in.

In order to make the information and experiences you have throughout your days become meaningful and part of insight, you need to make a habit of reflection. Doing that is as simple as cultivating a mindset of being receptive to all sorts of external data, and also engaging in the activities of conceptualization and experimentation as you encounter new pieces of information.

Building a Reflective Learning Process

In order to really harness the power of deeper learning, you need to engage in the deeper processes of reflection and abstract conceptualization. There are myriad ways to do this, so I would like to focus on a few best practices to help you build the foundation for a process of insightful reflection and make it a habit.

Maximize the Breadth of Inputs

Learning begins with input, and usually, that takes the form of concrete experience. Reading a book, a discussion with someone, watching a video, listening to a podcast — all of these are avenues available to us. But there are so many more possible inputs.

Effective learning begins with widening the scope of learning inputs. Every activity you engage in is an opportunity for the concrete experience at the beginning of the learning cycle. Take your drive to work for example. If you’ve been doing it for years, you likely just let the signs and buildings zoom by you with little thought. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

Each of the things going on during that drive to work are inputs via concrete experience — possible beginnings of a reflective learning process. It simply takes fixing your attention on something in a way that admits some lack of knowledge on your part. Once you do that, you can then accept the input of that experience as the beginning of learning about something new. Take for instance the brick apartment buildings snugly next to each other on the street. Is there a law as to how close they have to be to one another? Who decides that? Why? Be a little curious about that, and it could begin a fantastic journey down learning lane.

If your drive to work is particularly boring, listen to a podcast, audiobook, or something like that. Be on alert for something that piques your interest, and remember it for future review.

Set Aside Time to Reflect

As the legend goes, George Shultz — who was secretary of state under president Ronald Reagan — would take an hour each week to lock himself in the office with only a pad of paper and pen. No interruptions, no tasks at hand to work on, just thinking.

Psychologists refer to this way of operating as the task-negative mode — where the brain is not directly fulfilling a pre-determined purpose. Rather, it is left to relax and go where the connections between your thoughts take it. It’s a mode of following the strands of thought in your mind, and taking the time to see whether and how they can be tied together in meaningful ways.

What the task-negative mode is really good for, though, is the abstract conceptualization work of the learning process. It’s during those times of quiet reflection and mind-wandering where the mind tends to make all kinds of connections between various inputs you received and your existing knowledge. It’s also where you hook up facts and pieces of discrete knowledge with meaning and purpose, which only serves to amplify the satisfaction of learning.

This tends to happen because of something neuroscientists and cognitive psychologists call the default mode network, disparate areas of the brain which hook up and work together when you’re not focusing on a particular cognitive task. Essentially, it’s the reason why you come up with great ideas in the shower. Operating in task-negative mode helps to get this network working. So when you set aside time to just sit and let your mind go, you tap into this network, and can cultivate its power to help you connect the things you’ve experienced.

Decompress

If you were to just sit down and attempt to begin a process of reflection and insight, you would find yourself pretty frustrated. Unless you’re superhuman, or just don’t care about much, you’re carrying some level of stress and a heap of thoughts and feelings with you at any given time during your waking hours.

There is a name fore the nagging thoughts and feelings that cloud the mind and literally put stress on the body. They’re called unconstructive repetitive thoughts. My guess is that you know them well. They pop up randomly — especially when you’re trying to focus — and bug you. They tend to be either negative, or have negative connotations (telling you that you need to do something), and they block the road to focused work.

Recent investigations hypothesize that these URTs — both immediately and over time — sap cognitive ability. By robbing people of their attention and contributing to negative cognitive cycles, as well as contributing to physiological stress (heightened cortisol, etc.), URTs can have pronounced effects on our well-being and our ability to think creatively and constructively.

If you’re skeptical about this, try a simple exercise. Sit and attempt to not think of anything. Inevitably, thoughts, feelings, memories, or other things will pop into your mind. Record each one. My bet is that after a few minutes, you’ll have a list of negative thoughts or thoughts about how you need to do something. Those have a tremendous pull on you — both cognitively and physically.

Finding a way to alleviate the pressures of these thoughts will be game-changer for most people. Luckily, there are many ways to do this.

-

Meditate

Consistent meditation (whether mindfulness, mantra, loving-kindness, or other) can reduce both the frequency and effect of these thoughts. -

Journal

Recording your thoughts in written form is effective in not only unloading these URTs, but also in allowing you to make sense of how they fit into your life. You can hash out emotions, obligations, and priorities — so you can more effectively take action in your life. -

Play & Exercise

Play is a great way to decompress — especially when your mind is under significant pressure. But you have to engage in the right kind of play. Competitive sports, where the stakes are high, the pressure is on, and quick-thinking under pressure is key — that won’t provide the benefits of free an exploratory play that allow your mind to relax and receive the benefits of physical activity. Physical exertion below the point of fatigue, with minimal mental demands, is the best way to leverage exercise and play for the benefit of mental decompression.

Use The Power of Analogy

One of the most effective ways to retain and better understand new information is to connect it to a more familiar piece of information you already grasp firmly. A simple way to do this is through analogical thinking — which is my personal favorite way to learn things.

When you encounter a new concept in some field of study you don’t know well, ask yourself what concept that you do understand well is like this concept. Just trying to figure this out is enough to do two things that help you learn better:

- get you more enthusiastic about the new concept

- provide you with ample questions to ask someone who knows the concept well (e.g.: hey, is this concept like this other concept that I understand well? No? Okay, hmm, let me think a little more…)

A robust form of analogical thinking is visualization. Visualizing things as you learn — and thinking of possible related visualizations of familiar pieces of knowledge — can go a long way to cement your newly learned concepts. The old mnemonic trick of thinking of funny images to match up with people’s names can also work with vocabulary in new area of study where you’re unfamiliar.

Write as If You’re Teaching

I attended graduate school for 4 years. That’s 4 years of intensive study with experts in the field — reading texts by other experts, and engaging in high-level discussions of the same topics constantly. But it wasn’t until I set out to teach that material to fresh undergraduates that I realized how much I still had to learn. When I had to write about the topics I thought I knew well for an audience that knew nothing about them — that was a deep learning experience.

As you learn a topic, take time to write about it for an audience that doesn’t know anything about it (be they real or imaginary). If you can confidently write about a topic for an audience of total novices, that should give you a firm grasp on the material. In most cases, as you set out to do this, you’ll stumble and find yourself unable to fully explain the material. You’ll end up reading more about it, taking more notes, and connecting concepts in a more dynamic manner — because you’re trying to pass along the information to others. You’ll also tend to be more enthusiastic about researching, because you know exactly what you’re looking for, and there is a purpose to your research.

The more reflective you become in your approach to learning, the better your learning will be. But reflection is a process and a mindset that needs the right background and the right habits to keep it active and effective. Maximize breadth of inputs, set aside time to reflect, decompress, use the power of analogy, and write as if you’re teaching to ensure that you cultivate a mind set up for reflective learning.