As we rush to foster the valuable goals of creativity and innovation, let’s not use the wrong means to achieve them.

I’ll be transparent with you: I majored in Philosophy in college. And now, I spend time in the business environment talking about productivity, improvement, and innovation. Did I make a mistake? Absolutely not.

On paper, my choice of major had little connection to the business world. But in practice, it has everything to do with it. The freedom of philosophy allowed me to explore the limits of creative and innovative thought — unencumbered by most practical concerns — at least for a while. It’s the same type of education I received as a child. Free from talk of turning education in to profit, free to explore, learn, question, and create.

But that was the 80s and 90s — we were so naive, right?! Fast forward to today, when there is more and more of a push for entrepreneurship to be the paradigm in early education. Teach kids to think in terms of profit, loss, growth, scale, and markets — and we’ll have a million of the next Elon Musks! They say.

I’m not so sure. In fact I think that approach may well backfire — badly.

How the Entrepreneurial Model Constrains Thinking

I chose the major I did because I wanted to make a living playing with ideas. But I didn’t want my play with ideas to be corrupted by concerns about what was the most practical idea, what would get the most grant money, or what would be the best way to fuel the profit margins of a new or existing company. My intentions were pure. I wanted to explore the depths of the most abstract and confounding questions — and attempt to find answers for them. I wanted to be able to do that freely, and without regard to any other goal save finding the truth. How naive of me.

Enter the age of the entrepreneur. My kids, and my friends’ kids are going to be raised in an environment where entrepreneurs are the heroes and idols. They will be bombarded by Shark Tank competitions at their schools, and kids their age starting companies and shipping products or apps.

I have no problem with the aspect of this that focuses on nurturing creativity and innovation. What I do have a problem with is that the message is delivered with an undeniable and explicit connection to turning a profit.

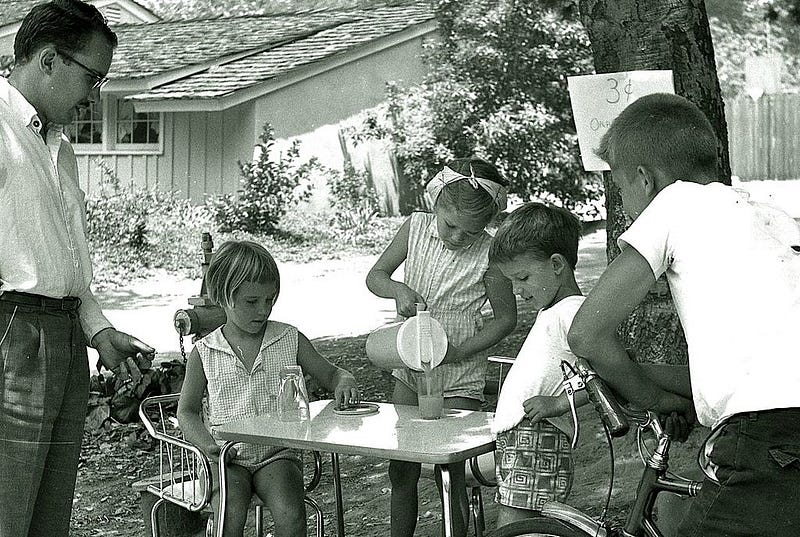

My reason for being circumspect about this profit motive is that I fear that an idea explored for profit is an idea only partially pursued. What I mean here is that kids need to be able to play with ideas. By “play” I mean free play, where the following things are true (courtesy of Dr. Peter Gray):

1. It is self-chosen and self-directed

2. It is activity in which means are more valued than ends

3. Play has structure, or rules, which are not dictated by physical necessity but emanate from the minds of the players

3. Play is imaginative, non-literal, mentally removed in some way from “real” or “serious” life; and

4. Play involves an active, alert, but non-stressed frame of mind.

The key here is that free play is about play in a zone removed from clear and decided goals — especially those placed on us by the business world (profit and growth).

So yes, let’s get students excited about creativity and innovation — let’s train them to do those things. However, let’s not make the mistake of thinking that the way to do that is to lure them in with entrepreneurship — which is centered around the constraint of profit-seeking.

Even Entrepreneurs Used to Be Something Else

Learning entrepreneurship has its place, but its place is not as the basis for learning about creativity and original thought.

When the goal is profit, the ideas will all start to resemble one another — which doesn’t sound either innovative or creative. When the goals are relaxed, and the mind is allowed to roam free for a while, we’ll be amazed by what the young minds bring back to us.

Does this sound crazy? It shouldn’t. For two reasons:

- One of the most innovative and disruptive companies — Amazon — has famously not turned a profit for most of its existence. It now rivals Apple for market capitalization.

- We should still believe in the division of labor. Thinking of original and creative ideas happens in one type of mindset. Thinking of how to take great ideas and make them profitable happens in another. When you try to combine them into one mindset, both suffer.

Let Me Be Clear

So what am I saying? Am I saying that we should forget about profit and just let kids think about whatever and see what happens? No — of course not.

What I am saying is that there is a such thing as the hedonistic paradox — which is roughly this: if your only goal is pleasure, you tend to have a much harder time actually deriving pleasure from anything. In other words, if pleasure is your goal, you will only really get pleasure if your aim is at some other goal. Achieving that goal will then give you pleasure.

I suggest we recognize that the same thing might be true with profitable ideas. The more we try to think of our ideas in terms of immediate profitability, the less creative we will become — and the fewer profitable ideas we will inevitably think of.

Let’s not stifle the next generation by making them all think like entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship is exciting precisely because people bring in all sorts of background experience into it. The more we try to mold the next generation based on current entrepreneurs, the worse off future entrepreneurship will be.