One of the very first classes I took in college began with the professor saying something like this:

If you leave this class with more questions than answers, I’ll have done my job. I’ll have given you all you need to keep learning — curiosity.

It was in this way that I came to understand that one of the most important qualities that anyone can have is curiosity. That genuine curiosity — the kind where you truly yearn to understand something — has to begin with admitting some lack of knowledge. In order to really become more intelligent, you have to sincerely admit that you’re ignorant.

When I began teaching several years ago, I used the same line at the opening of each semester of Philosophy 101. Some students loved it, and some thought it was lame. They wondered how I would help them become equipped for the knowledge economy without giving them any answers.

Axes of Ignorance

I informed the incredulous students in my class that they were taking me too literally, but no seriously enough. I was going to arm them with knowledge, and expertise, but those don’t come in the form of answers.

There’s a paradox at work here: the more of an expert you become in some field, the more questions you tend to have about it. I think that this has something to do with the relationship between the awareness of ignorance, curiosity, and enthusiasm.

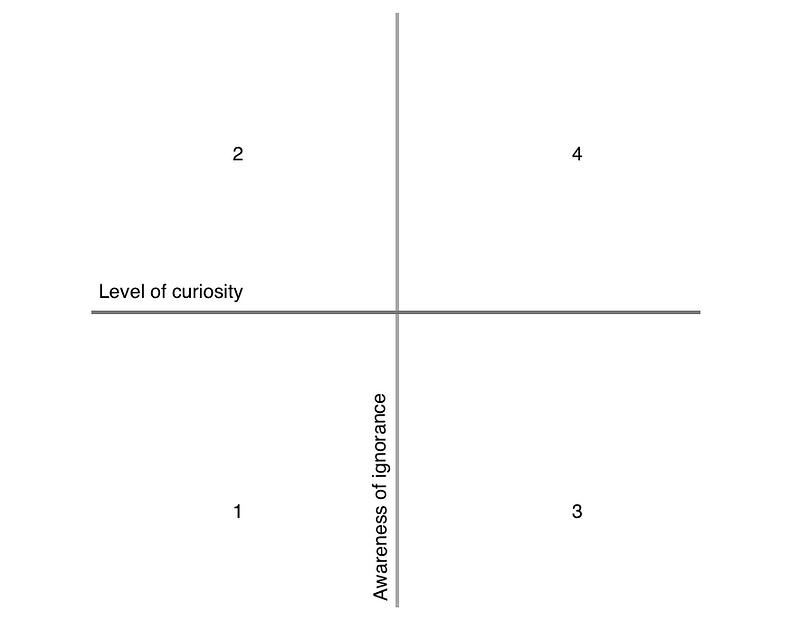

The x-axis represents your level of curiosity, from not at all curious, to intensely curious.

The y-axis represents what I call your “awareness of ignorance” — meaning how well you know your deficiencies in knowledge, or how well you know what you don’t know.

Throughout your life, you’ll find yourself in one of the 4 quadrants regarding any given topic:

-

Quadrant 1: Unknowingly ignorant, and not very curious

(i.e., don’t know what you don’t know, and don’t care) -

Quadrant 2: Knowingly ignorant, but not curious

(i.e., you know what you don’t know, but you don’t care) -

Quadrant 3: Unknowingly ignorant, but curious

(i.e., you don’t know what you don’t know, but you care) -

Quadrant 4: Knowingly ignorant, and curious

(i.e., you know what you don’t know, and you care)

We start our lives in quadrant 1. We don’t know what we don’t know, and we don’t care. Slowly, we begin to understand that we don’t know how to do all sorts of things that adults are doing: walking, talking, grabbing things, etc. We’re then in quadrant 2. Once armed with that awareness of our ignorance, we develop curiosity — we care about getting to know those things. We find ourselves in quadrant 3. We then seek to learn them. But by that time, we become aware of so many other things we don’t know. We find ourselves in quadrant 4.

We repeat this process for every new subject we stumble upon. It’s a repeating cycle.

Get Out of Pac-Man Mode

This is important because becoming smarter is not actually done by way of being a mental Pac-Man — just looking to gobble up a bunch of bits of facts and data. Getting smarter is most effectively done when it’s approached by looking at what you are ignorant about — what you don’t know. There is a point at which that list of things becomes large enough that you want to start slimming it down, and you become curious about one of them.

But here’s the kicker: the more you end up learning about a subject, the more you end up realizing you don’t know about it. In other words:

the most productive search for answers actually results in more questions.

The process then becomes:

- awareness of ignorance

- curiosity

- questions

- some answers

- more questions

- repeat

Things brings me to the most exciting (or disheartening, depending on your view) thing about knowledge and learning. If I’m right about this question-yielding process, the quest for knowledge is about crossing the y-axis, into quadrants 3 and 4. That means that learning is about first admitting ignorance, and then becoming curious. It also means that teaching involves the same things.

Maybe this is a n0-brainer to some of you. But I wonder how often we forget to approach both learning and teaching in this way. How often do we begin reading a book or article by listing things we don’t know, and then questions we’d like answered? How often do we finish reading by doing the same thing? Probably not often.

But why? Aren’t we curious enough? No. We’re still in Pac-Man mode — still looking for the next bunch of facts to gobble up. After all, we want to show off how many books and articles we read, right?

Like anything else, learning is actually more in the prep-work than the actual ritual — more in the practice than in the game. That means that learning is more in the stoking of curiosity about things than in the collecting of information. It’s more in contemplating the questions and the longing for answers than in the reading of the books.

So let’s try to admit how ignorant we are, get curious, and get learning.

Did you find value in this piece? Consider subscribing to my weekly newsletter — Woolgathering. It’s one email per week, with interesting stuff to ponder, from me and from around the web.