Two Simple Practices to Forge a Healthier Path

There are times when I wake up and from the jump, I feel like I’m way behind. I feel like I’m in slow motion. I feel like I’m already stumbling through the day. I spill coffee everywhere. I skip working out. I fail to catch up on emails before the new ones come rushing in. I don’t write a damn thing. I feel like I’m just buried.

I have the drive, I have the dreams, I have the goals. But I struggle. I stumble. I fall behind.

And what’s worse, I see all these people around me who seem to be crushing it. They’re organized, they’re ahead, they’re making an impact. I’m just watching from the sidelines, and I’m cursing myself for not being further along.

I’m assuming that many of you feel the same way from time to time.

So why does this happen? Why do we get so disheartened by all of this success around us? Why is it so hard to just keep going — to carry on? Allow me to offer up two possible reasons:

-

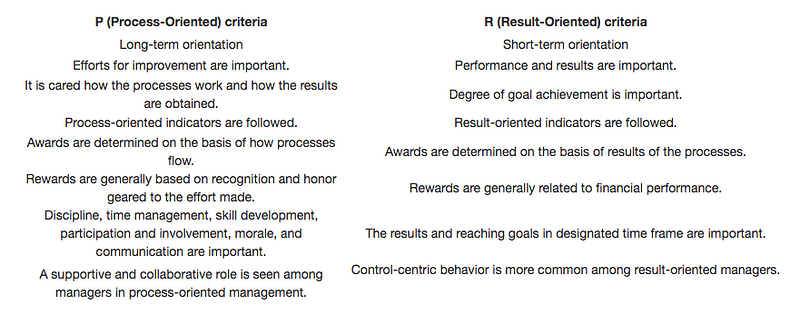

We’re doing too much — we just don’t know it.

Often times we are trying to do too many things at once. We think we’re just doing one project, so that should be easy, right? But actually, each project involves a lot of things: analyzing, organizing, planning, brainstorming — and we often try to do these all at the same time.

These are all different job descriptions, with different workflows, and they get in the way of one another. So when we do these myriad other things — at many times unknowingly — we exhaust ourselves. We scorch the earth behind us, and make it that much harder get things done later on. -

We let unrealistic expectations and desires govern our relationship with ourselves.

We expect a lot from ourselves. We expect both a lot of volume and a lot of quality work. We also tend to also expect it quickly. As anyone in quality control or project management can tell you, you can’t have all three of those things. For one thing, when you have desires and expectations of creative work right off the bat, in what way are you allowing yourself a free and stress-free environment in which to really create? Sure, you may well have a goal — something you want to convey with your work — but at least until you gain momentum, don’t let that goal be a set of shackles on your process.

A Simple Suggestion: Be Radically Compassionate With Yourself

The problem with making mistakes, falling behind, and procrastinating is that it’s like a nuclear bomb. It’s bad enough that the blast is loud, bright, and destructive, but it’s the after-effects that actually do the worst harm. We fail, we fall behind, we mess up, and that is bad enough. But what is worse, we then proceed to beat ourselves up about it. In some instances, the beating is long and drawn out. There is a lot of negative self-talk.

So in terms of solving the problem, two things need to happen: Radical Acceptance and Radical Compassion.

Radical Acceptance

You are going to fail, fall behind, etc. There is no getting around that. You must accept that. Period. That is step one.

But this is tougher than it sounds. You have to accept that these things will happen, accept that you are not exempt from them, and accept that when they happen, they don’t make you any less valuable or deserving a person. This does not happen overnight.

In fact, those who have lofty goals, seek high performance, and devour the most self-improvement literature tend to be the toughest on themselves. They may screw up a lot, but for some reason, they hold themselves to absurdly high standards. As a result, they judge themselves too harshly when they fall short.

Radical Compassion

Step two, then, is to then refuse to beat yourself up about the inevitable mistakes, missteps, or bouts of procrastination. Instead of engaging in the negative self-talk, stop and allow the wave of negative emotions to subside — almost literally like a wave.

Most of our mental chatter is negative; it’s a real problem. The voice we speak to ourselves in tends to be critical, unsupportive, and thus obstructive. We think we need to be hard on ourselves, to push, to work hard. But you can push and work hard without being hard on yourself. In fact, it’s much easier to push and work hard if you don’t constantly beat yourself up for falling short or being burned out.

An Exercise in Radical Compassion

One of the newer waves of behavioral therapy is called ACT, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. One of its creators, Stephen C. Hayes has an interesting exercise wherein he asks us to imagine ourselves as a child:

Acceptance is taking in your history as it is … much like giving that child a hug. The compassionate part of us would not slap a child for feeling fear or sadness, yet we do the functional equivalent so readily to ourselves as adults.

…the only way the child part of us can be listened to, respected, loved, cared for, and allowed to play is if the grown up part of us chooses a vital and self-compassionate path, that acknowledges pain and yet carries it forward into a life worth living. It is sometimes hard to find a place to do that for ourselves. If that is the case, there is an alternative. Imagine yourself as a child, and a time when a hurt you are feeling now was first being felt. Do it for that child.

This exercise can work wonders. Imagine yourself as a child, at a time when you felt sad, vulnerable, when you were looking for support, approval, and compassion (as we all were as children).

Imagine yourself as that vulnerable child every time you stumble and get mad at yourself, because deep down, you still are that child. Your emotions are still there, you just ignore or denigrate them. The less you do that, the more compassionate you will be with yourself. The more compassionate you are with yourself, the less likely you will participate in a cycle of anxiety and burn-out. That’s the foundation of sustainable personal growth.

Did you find value in this piece? Consider subscribing to my weekly newsletter — Woolgathering. It’s one email per week, with great ideas to add value to your life and work.