I was a GTD fanatic for over 10 years, but when I realized it wasn’t giving me what I needed, I had to build my own system

Photo by Kate Trysh on Unsplash

For the first 10 years or so of my working life, I was a huge GTD adherent. At times, I was more than an adherent, I was a fanatic. It seemed like the perfect system to me. I loved ubiquitous capture (and still do, as a matter of fact). Understanding the world in terms of projects and next actions seemed intuitively right to me. And to an extent, it still does. The concept of the weekly review appealed (and still appeals) to that part of me that knows how good it feels to really think deeply about the stuff of your life and plan to take care of it.

But for all that love I felt (and still feel) for GTD, I’ve had to come to grips over the past few years or with something that I just wasn’t able to get from it. There was a piece missing — 4 missing pieces, actually — that in my years of using the system and systems like it, I just couldn’t find in it.

Prioritization

GTD was great about telling me what I needed to do and in what settings I could do it. But it wasn’t great about helping me decide when to do things. I had all these projects with associated actions, and contexts, but no idea when I should do them — or even if I should do them at all.

This problem of if and when is a problem of prioritization. Understanding which items are priorities for you helps you understand when they should get done.

Focus

I’ve struggled all my life with staying focused. There are various factors that affect my focus, but one that’s been fairly constant is being overwhelmed by how many tasks I have to do. And because I’m very visual, a long list of tasks and projects makes my inability to focus that much worse.

Motivation

Systems like GTD are great at getting me organized and prepared. By getting my projects and tasks straight, I was able to see what needed to be done. But what these systems didn’t provide was a way to motivate me to push through and get those things done. It’s not that these systems fell short. They weren’t built with that in mind, or they were built under the assumption that being effectively organized and prepared was motivation enough to get things done.

Measurement

What gets measured gets managed. Feedback is necessary for consistent improvement. While systems like GTD were always great at setting me up to get to work, they didn’t provide me with much in the way of measuring how I was doing. The more I can see — in something close to objective terms — how well I’m doing at getting important things done, the more I can keep improving.

Disclaimers

Here’s a disclaimer: I’m not saying that you can’t get these 4 things out of GTD or other systems. I’m just saying I wasn’t able to. And because it’s highly unlikely that I’m the only one, I feel it will probably be useful to share how I built my own system to get those 4 things I wasn’t getting from GTD and other systems.

What has ended up working for me is a deceptively simple system. It’s built on a set of tweaks to the principles of systems like GTD. But it also adds important elements to it. It starts off with a very simple daily ritual that provides focus, prioritization, motivation, and measurement to the day. It can build out from there into a more all-encompassing system, which integrates those elements into your life. It’s done exactly that in my life.

Here’s another disclaimer: personal productivity is just that, it’s personal. So it’s never wise for someone to say that a given system will make you more productive. In line with that principle, I will not say such a thing here. All I will say is that this system has helped me be productive in ways no other system could. And it was simple to set up and is simple to keep running. I hope that perhaps, if you’re looking for a simpler system that supplies these 4 missing elements I mentioned, you’ll give this a shot.

The Today System

To review: I needed a system that could deliver the 4 missing components that my years using GTD and other systems didn’t provide.

- A way to systematically prioritize my tasks each day and represent those priorities in a tangible way

- A mechanism to help me focus on what I need to do today — beyond just what’s on my calendar.

- A source of motivation throughout the day

-

A measurement system to tell me how good I am at doing what I’ve prioritized, as opposed to just crossing tasks off of a list. Also, that measurement system should serve as the basis for a feedback loop that helps me evaluate and improve my performance over time.

So I built the system. It’s called The Today System. It’s built around a simple 3 x 5″ index card that you fill out every day.

It’s easy to start using right now — whether you’re a productivity newbie, or a seasoned veteran. It’s easy to integrate into existing productivity systems. It’s also easy to scale up into a more complete system by adding other components as you get more comfortable with using the card each day. It’s not an all-or-nothing system; you start with a card each day, and build your system as you go.

So here is the high-level overview of the elements system:

-

The Today Card – A card each day with my most important items, and a score for them that reflects their relative importance. It’s a physical card — separate from all of my lists, calendars, and apps — to help me focus. The scoring system helps motivate me to complete the items on the card — so I can get a good score.

-

The Simplified Scheduling System (S3) — A list of my tasks — arranged by relative timeframes in which I’m aiming to get them done: today/tomorrow, next few days, this week, and next week and after.

-

The Scorekeeping Sheet — Which records my daily score from the card, as well as notes about the day. It also calculates my score for each week and compares it to last week’s score. It provides me with space to reflect on my performance and plan for how to do better in the future.

-

The Projects List — A list of things bigger, more complicated, and happening on a longer timeframe than the actions on the S3. Most of the items on the S3 will fall under projects.

-

The Goals List – A list of my overarching goals — the big dreams or aims I have over the next 2 – 20 years. Each goal has a #G and a number next to it. I then mark each of my projects with the #G number to note which of my goals that project is serving. It lets me see which projects are not serving my goals — which helps me more effectively prioritize.

So let’s dig into it.

How to Set Up the System

As I say above, the system is not all-or-nothing. I began the system with what I call Level 1, just an index card with my most important items, and the possible points listed. That alone was enough to help me prioritize what I intended to do each day, keep me focused on it throughout the day, and motivate me to achieve just a bit more than I would have otherwise.

But once I had been filling out a card every day for a while, I built out a more integrated system. It has 4 levels — each of which builds upon the previous one.

-

Level 1: The Today Card

-

Level 2: The Today Card + The Simplified Scheduling System (S3)

-

Level 3: The Card + The S3 + The Scorekeeping Sheet

-

Level 4: The Card + The S3 + The Scorekeeping Sheet + Sorted Goals & Projects List

Below, I’ll run through each of the levels, and what they look like. Feel free to stay at one level for as long as you like — until you feel like you’re ready for

Level 1: The Today Card

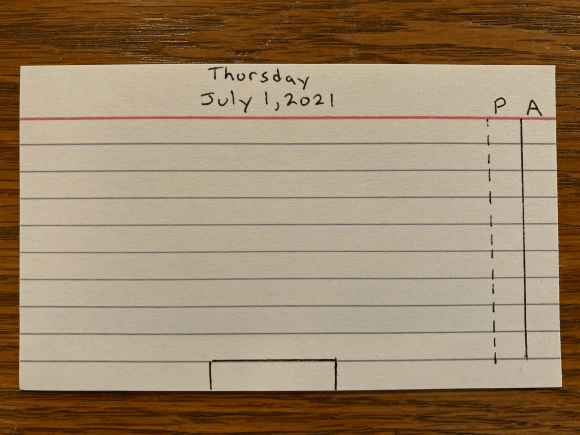

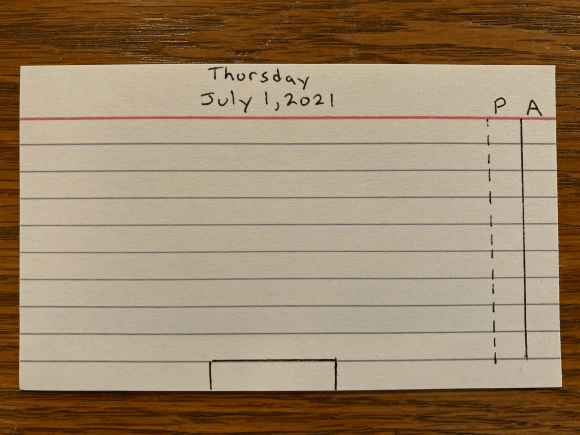

Grab a 3″ x 5″ lined index card and something to write with.

- Flip the card to the unlined back, and position it vertically. Set a timer for 3 minutes, and write down every task you think you might need to do today.

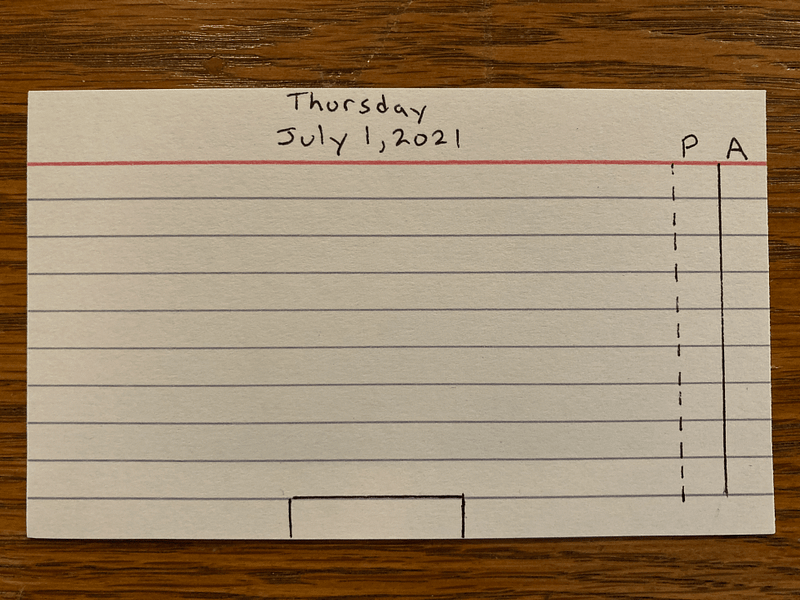

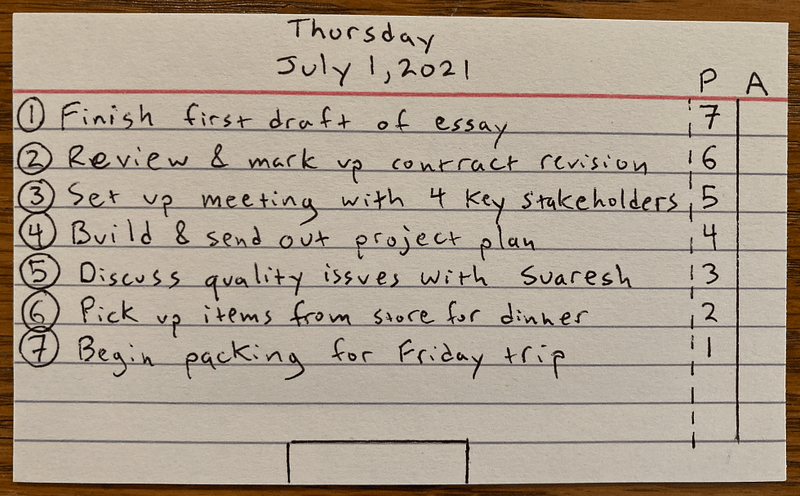

- Flip the card over to the lined side. Put today’s day and date at the top, and make it look like the picture below.

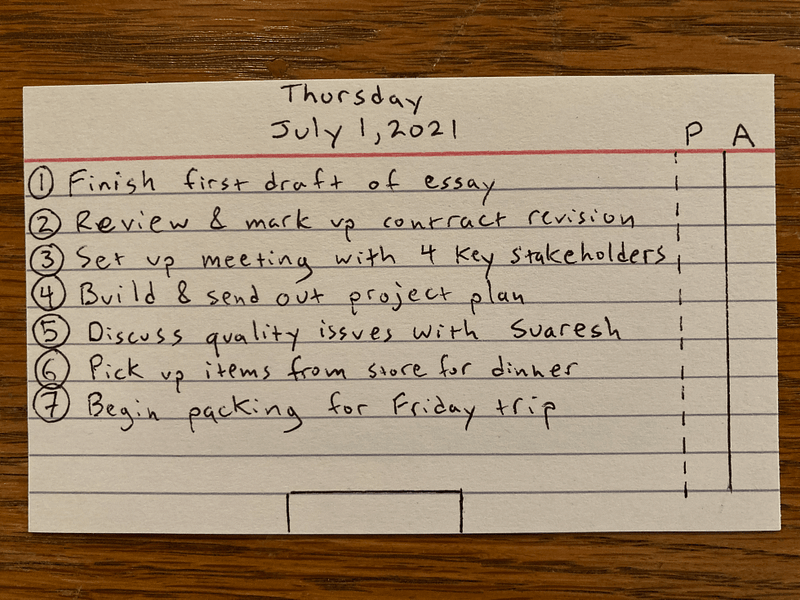

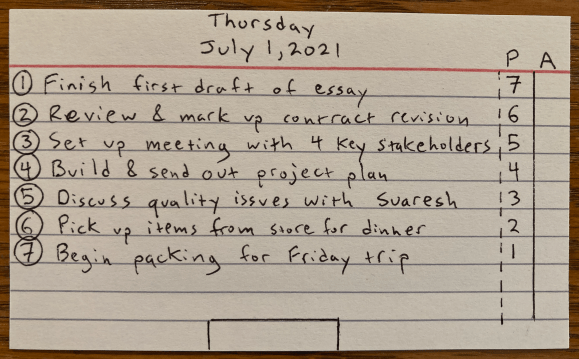

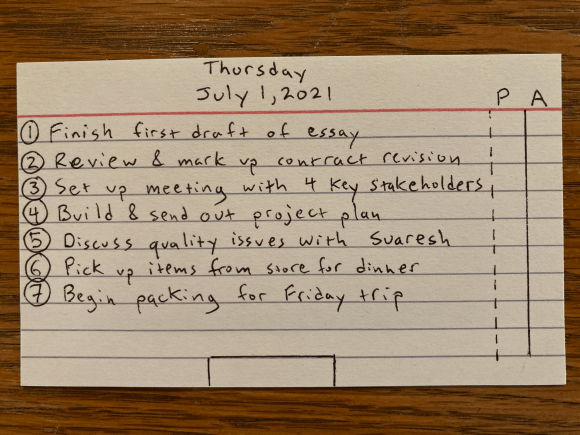

- Using your task list from the back, begin writing your most important tasks you have time to do today¹, in order of importance.² Pick no more than 9 tasks (one for each line). The first item is #1, and so on. Your card should look like this:

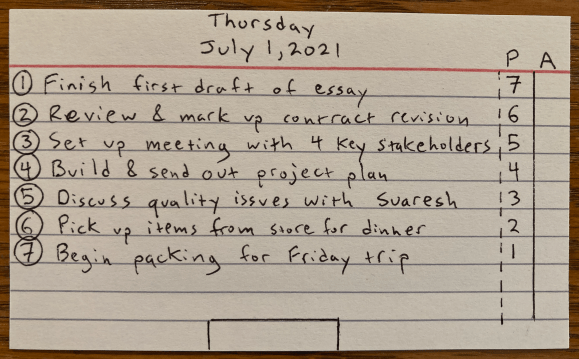

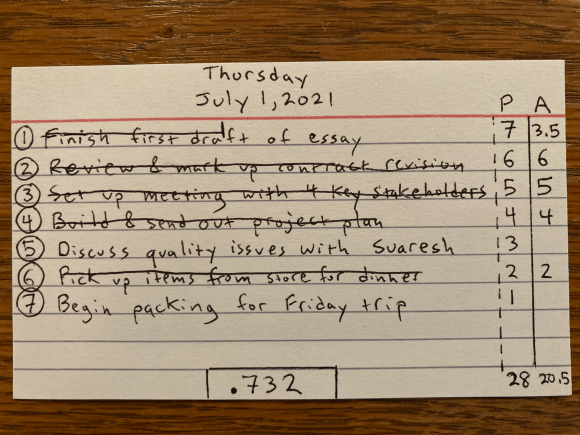

- In the “P” column, place the point value for each item using the following scheme:

– Item #1 gets a point value equal to the total number of tasks on the card.

– Item #2 gets a point value equal to 1 less than the item above it.

– Repeat until you get to the final item on your list, which is worth 1 point.

Your card should look something like this:

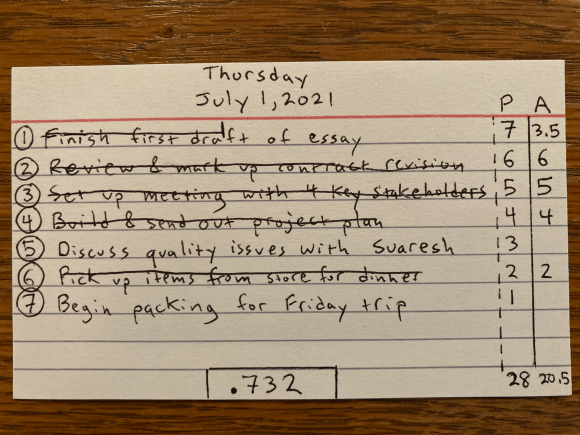

- Add up all the possible points in the “P” column. That’s your possible points value for the day.³

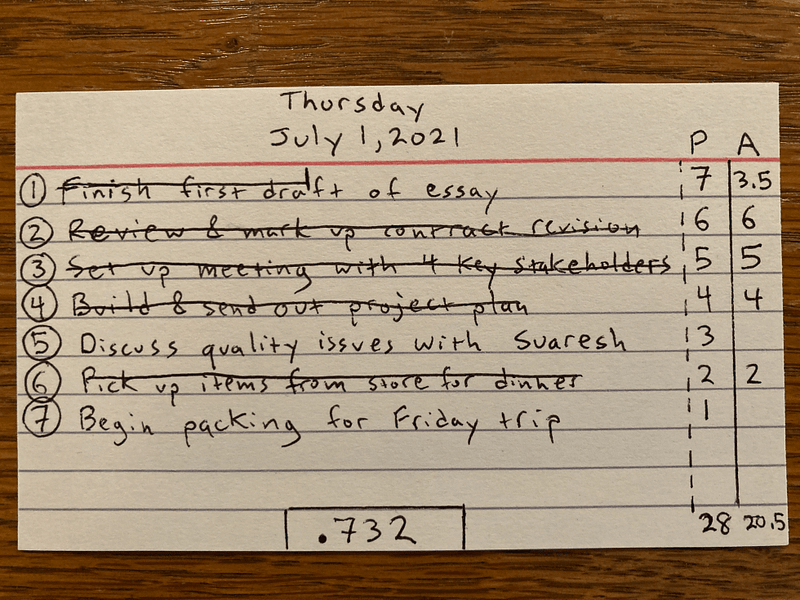

- As you complete items, cross them off the list, and award yourself the point value for each in the “A” column.⁴

- At the end of the day, add up the total points you’ve earned, and place that at the bottom of the “A” column. Take that amount, divided by your total points possible, and put that in the box at the bottom of your card. Below is an example of a fully scored card.

Aim for a score of .750 or greater. If you achieve that, keep it up! If you score lower, think about fewer items per free hour tomorrow. Repeat each day.

Level 2: The Card + The S3

Just filling out a card with the most important items to take care of, and aiming for a high score each day, was a huge help for me. But it was even more helpful to have a list of tasks lined up that I could put on my cards each day.

You could use a standard GTD-style “next actions” list — unordered and perhaps with contexts (like “@office” or “@phone”). But for me, that proved to be too overwhelming. I needed a way to queue up the things I should be working on first, things to work on after that, and further down the line. So I built what I call a Simplified Scheduling System, or “S3”.

A Simplified Scheduling System (S3) is a list of all the things you want to get done, separated into 4 temporal categories:

-

Today +

(this list feed the card each day)

The items you deem most important to try to get done today, or tomorrow, if you don’t think you’ll be able to get them all done today.

-

Next Few Days

The items that should get attention during the next few days. They should move up as items get on to the Today Card and get completed.

-

This Week

Items that should get taken care of in the next 7 days or the current week — however you define that.

-

Next Week and After

This category is more of a parking lot for things that need to be on your radar, but not quite yet — at least until other items this week are taken care of.

If you don’t have a list of projects already, the S3 is simply your place to dump all the things you need to do as you become aware of them. As you complete items, or as they become more important, move them up the schedule. As things become less important, move them down.

It helps to review the S3 regularly. How you gage where items need to be in the list is up to you. But don’t let that list go stale. It should reflect — at any given time — the relative order of importance of tasks in the queue.

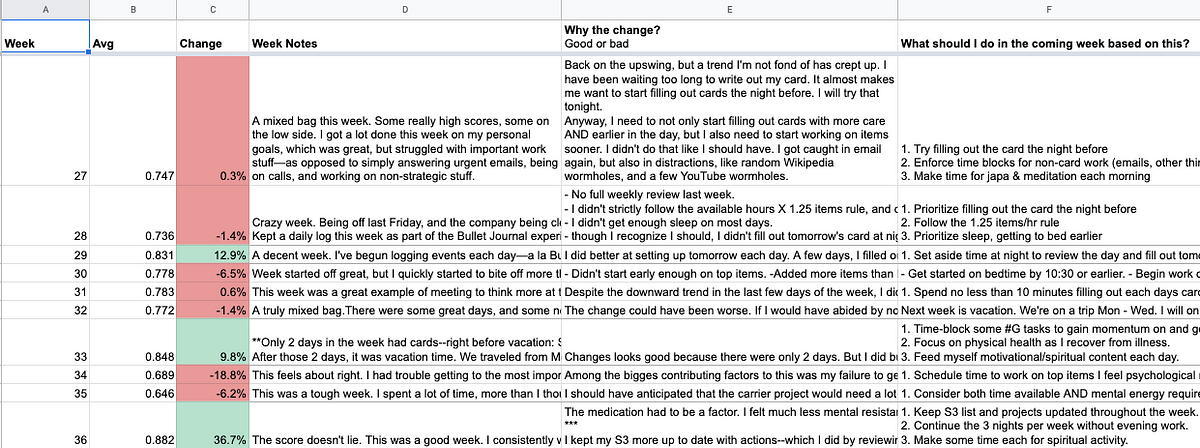

Level 3: The Card + The S3 + The Scorekeeping Sheet

Below, I reference a Google Sheets spreadsheet. You can find a copy of the template to use here.

Filling out a card each day, and keeping an updated list of roughly scheduled items is already super helpful. The gamification of each day was a huge boon to my productivity. I found myself pushing to get the best score I could each day — based on the items and possible points on my card.

But after a while, I became more interested in tracking my longer-term scoring trends. For instance:

- how am I doing over the course of a given week?

- how does my score for this week compare to my score from last week?

- what’s my career score?

- what can I learn from all these trends that I can put into action going forward?

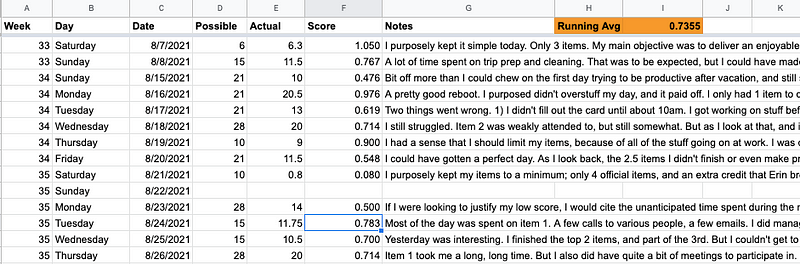

For the purposes of answering these questions, I created a Google Sheets spreadsheet with 2 tabs. (You can download a template here.)

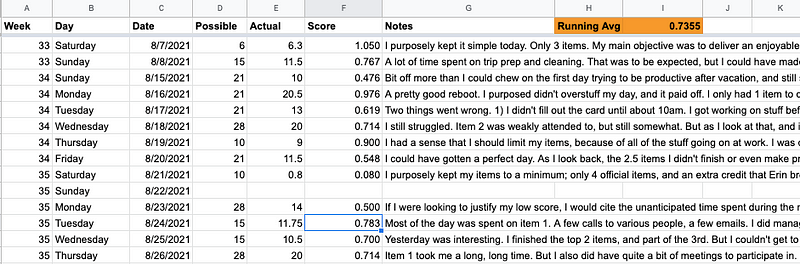

The first tab is a Daily Scores tab. It simply populates the week number (1–52), the day and date, and the provides a space to input the possible points for each day, and the actual points earned each day. It then calculates the score for the day. The last column allows for notes about the day — which I use to record my thoughts about how it went. I usually explain why I got the score I did, and what that might be telling me.

A screenshot of the Daily Scores tab from my own personal scorekeeping sheet

In an orange cell up top, it has a formula that calculates my “running average.” It’s the sum of all the points earned divided by the sum of all the possible points. I personally place a lot of importance on this number. If I can get that lifetime score to at least .750, and keep it there, I consider that doing quite well.

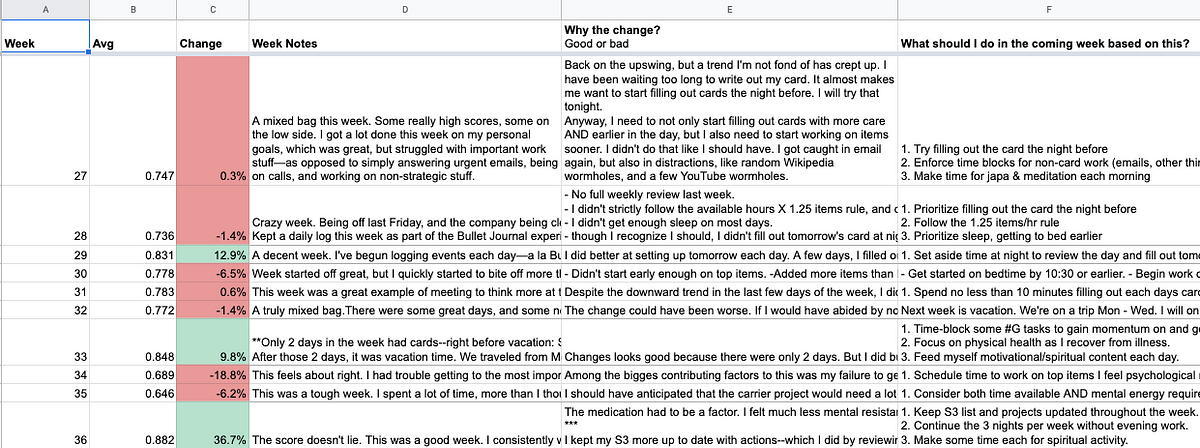

The Weekly Notes tab is for reflecting on your week-over-week performance. It automatically calculates your score for each week (using the week number column in the Daily Scores tab). It calculates how your score this week compares to last week. It also has columns for 3 key pieces of reflection to make sure the score serves as something actionable.

- Week notes

- Why the change from last week to this week?

- What should I focus on in the coming week to sustain or improve my score?

A screenshot from the Weekly Notes tab in my own personal scorekeeping sheet

Much like GTD, the tab should be part of a weekly reflection process. It’s much simpler than a weekly review in GTD, and it’s more like a combination of a journal and a quantitative self-analysis, combined with a forward-looking plan of attack for the coming week.

Level 4: The Card + The S3 + The Scorekeeping Sheet + The Goals/Projects List

Even at Level 1 — just filling out the daily card — the concept of importance is central. That is, the most important tasks you’re aware of should be on your card today. And the most important of those tasks should be at the top of your card. The more important the item, the more points it’s worth.

But how do you figure out what’s important? You can rely on your gut — which at times can be a pretty good guide. Or you can systematize things a bit more. That’s where Level 4 comes in.

Level 4 is about doing more than just tracking the tasks in your life. It’s about tracking your projects (which involve multiple tasks), and sorting them into those that directly serve your goals and those that don’t.

Just like getting any old tasks done isn’t a great measure of productivity, neither is simply getting any old projects done. But getting the right projects done — and getting the wrong ones off your plate — is what productivity is all about.

I have 4 major, long-term goals at the very top of my list of projects. As I review my projects each week, I ask myself which projects serve those goals, and which don’t. By each project that directly serves one of my goals, I put a #G next to it. By those that don’t, I put an #NG. I try to minimize the amount of #NG projects that stay on my list.

My S3 list contains primarily items that fall under #G projects. And when I fill my card out each day, the top 2 items on the card (those worth the most points) are actions that serve #G projects. My goals dictate what’s important, which dictate how much things on my card are worth. So my score each day, each week, and beyond reflect how much I’m serving my goals each day. That is the very definition of productivity — spending each day working on your goals.

In Conclusion, and One Final Pleasant Side Effect

I’ve been using this system since November 30, 2020. I fill out a card each morning. I grade myself based on the points I get each day. I record the daily and weekly progress and reflection in my scorekeeping sheet. I share my card each day on our little Today System community — and others do the same.

In that time, what I’ve found is that not only do I have the ability to focus, prioritize, and stay motivated that I never did before. But I also gained a helpful side-effect. It’s one that became apparent early on, and it’s become the main reason why I fill out a little index card every morning.

I now have a feeling of self-confidence — and it’s backed by a number. And the number doesn’t lie. You may have caught that lifetime score in my screenshot above — the number in the orange cell of the “Daily Score” tab of my scorekeeping sheet. It’s at .7355.

That means that about 74% of the most important things I say I’m going to do each day — I get them done. Come hell or high water (which — as most of you know — do come), I follow through on what I say is important. Say what you will about measuring yourself, but I think that’s a pretty damn good way to do it.

If this sounded at all appealing to you, come check out The Today System on the web. Join our community on Discord. Sign up to learn how to use the system, and to get regular emails from me with tips, tricks, and helpful insights.

Notes

- Don’t overload yourself with tasks to do, especially if you already have things you’re committed to doing/attending today. A good rule of thumb is this: count only the amount of hours you have free to do tasks today (i.e., not time in meetings, running errands, cooking dinner, self-care, or other pre-existing commitments). Take that quantity of hours and multiply it by 1.25. That’s roughly the number of tasks that should go on the front of your card.

- I take the word ‘important’ to mean a task that contributes to meaningful life goals of yours — things that you consider worth doing in order to make your life better. While others’ goals for you may seem pressing (like getting your boss some document she requested), don’t assume that automatically makes them important.

- A quick way to add up your possible points is to use a fun mathematical concept called the termial. Simply take the count of the items on your list (in our example, it’s 7). Multiply that by the count of items plus 1 (in our example, that would be 8). Then divide that by 2, and that is the total possible points.

- Half points are possible for items that you put forth a respectable amount of effort toward, but didn’t complete. For example, if you had 9 items on your card, and you made progress on item 1, but didn’t finish it, award yourself 4.5 points.