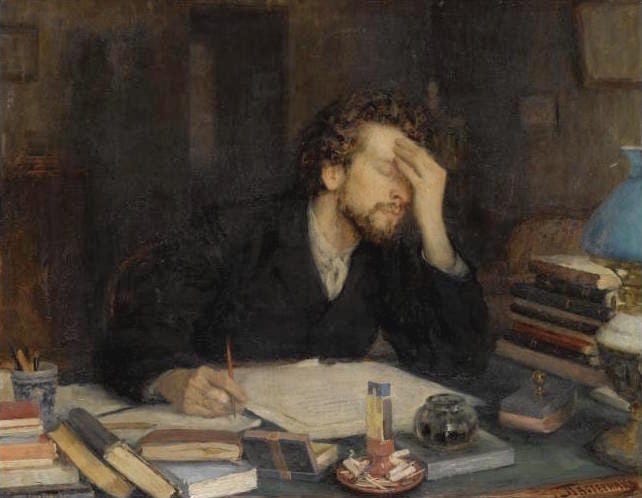

“Throes of Creation” by Leonid Pasternak

Your progress is not on the page

If you’re writing online, and you’re anything like me, you probably care about how many people see your work. You also probably care about how many people publicly like your work (recommends, likes, retweets, etc.). You probably also read work by authors who publish what seems like an endless stream of stuff, all of which gets a lot of public likes. You think to yourself: they’re making progress, but me, I can’t even publish regularly.

I used to think this. In my worst moments, I still do. But as I’ve begun to write more (not necessarily publish more, just write more) I’ve learned something. There is a difference between the media and the message (despite what Marshall McLuhan may have said).

As a writer, I’m not doing typography; my words are not the object of my pursuit. I am trying to convey a message, and if that message is good enough — if it’s one worth conveying, I should be able to delete sentences and paragraphs in the service of conveying that message. But of course, I am weak. Each of my sentences is a unique and beautiful snowflake; each my only child, who I cannot bear to let go.

This is a symptom of a larger, misguided attitude about progress in art or creative work. We often think that what we have on paper, on canvas, or what has been published, represents the only progress we’ve made as creatives. That is simply not true.

The real progress that an artist or creator of any kind makes is largely invisible. It is the progress of thought — the evolution of ideas, and it takes place through and manifests in the final product, but that is not where it lives. It lives inside the mind of the artist.

More specifically, progress lives in that space where the artist’s mind conceives of the world — where it makes sense of the world. This is why those who fetishize output and the crossing off of tasks are often confounded by the radical creatives tossing out hours of work and spent materials, only to tear it up and start again. They mistakenly think that the real progress lived there — in those deleted words, in those shredded canvases. Again, they are wrong.

I say all of this to reassure you that deleting paragraphs, erasing or drawing over lines, getting rid of slides, etc. is not deleting your progress. It is adding to it. You can add by subtracting, and sometimes, the process of eliminating can be even better for your work than any kind of additions you could ever make.

That is why this piece is short — because I just have this one thing to say, and I think it’s very important.

If you know someone who’s struggling with their creative work, share this with them — not because I want credit for it, but because I want them not to feel as bad as I used to. There are those who have published millions of words, or put out hundreds of songs. That’s fine for them. That doesn’t mean you aren’t making progress.

Keep at it.