What you DO know can most definitely hurt you, or at least keep you from thinking of great ideas.

Photo by Jacalyn Beales on Unsplash

If you could snap your fingers and become an expert on something — anything — by tomorrow, would you? Most of us probably would.

It feels good to be the expert on something. People turn to you for answers. You become a “thought leader.” Your opinion is respected above most others’. You have the answers, and can solve problems that others can’t.

But is expertise all it’s cracked up to be? As it turns out, no — it’s not.

Expertise can actually be a barrier to creative problem-solving. Which means it can be a barrier to innovation and growth. The more you know, and the more experience you have, the harder it can be to come up with ideas to solve problems. It’s called the Einstellung Effect. And it was discovered in an interesting experiment.

Read on.

The Water Jug Experiment

In 1942, psychologist Abraham Luchins conducted an experiment to see how perceived expertise affects creative problem-solving. He found that if we solve a problem the same way a few times, we tend to keep doing it — even when it stops working.

What’s worse, our tendency to stick to one preferred way of solving a problem often blinds us to alternative simpler ways to solve it. Our expertise blinds us to better solutions. It also makes us give up more easily.

The Problem Set

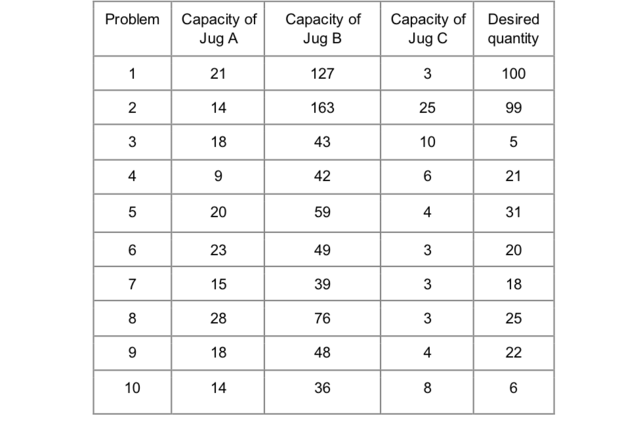

Luchins presented 10 problems to participants. In each problem, they would have to figure out how to get a desired quantity of water using 3 jugs of different capacities.

The chart below lays out the problem set.

source: Luchins 1942

So in problem 1, we’re asked to see how to get 100 ounces of water, using only jugs of 12, 127, and 3 ounces respectively.

For the first 6 problems, nearly all participants used the same method: B-2C-A. So for problem 1 in the chart, start with 127 oz. in jug B, then pour some of that into jug C twice, which gives you 121 oz remaining in jug B. Then you fill up jug A, which leaves you with 100 oz in jug B. Done!

This formula is indeed the most efficient solution for versions 1–5 of the problem. But once you hit problems 6 through 10, things get a bit trickier.

You can use B-2C-A to solve problems 6 and 7, but there’s a simpler way. Take problem 6 for example. You’re trying to get 20 oz. You could easily do that by taking jug A (23 oz.) and filling up jug C (3 oz.). Boom, you’re done.

How Success Blinds Us

Most of the participants were so conditioned to using the formula they had been using in problems 1 through 5, they used it for problems 6 and 7.

Things get especially hairy in problem 8. For problem 8, formula B-2C-A doesn’t work. But guess what does: A-C. Participants who were using B-2C-A were overwhelmingly stumped by problem 8, and failed to solve it.

Here’s the crazy part: Participants who tried problem 6 first overwhelmingly solved problems 6–10, using the simplest solution (either A-C or A+C). Why? Because they didn’t learn to use formula B-2C-A. They didn’t develop expertise and a rigid way of problem-solving.

How the Einstellung Effect Blocks Creativity & Innovation

Luchins’s experiment is an illustration of something called the Einstellung Effect. It refers to the negative effect that experience has on problem-solving ability. The more we solve a problem one way, the more we cling to that way of doing things.

In only 5 rounds, the participants became so fixated on one mode of thinking, they kept using it even when it was much less efficient. What’s even worse, when that same mode of thinking proved completely ineffective, participants concluded that there was no solution. They gave up.

The more we cling to one preferred way of doing things, the more we shut out other options — even to the point of giving up when our preferred options don’t work.

The Einstellung Effect is essentially a problem of expertise. Being an expert at something can actually be a disadvantage. It can make you less likely to come up with effective solutions to problems.

We tend to value expertise because it means that someone has both experience and knowledge. So we tend to turn to experts to solve tough problems. But Luchins’s experiment shows us that expertise can actually make it more difficult to solve tough problems.

Expertise tends to produce rigid thinking — close-mindedness. Rigid thinking stifles creative thinking and innovation.

Functional Fixedness

There’s a problem related to the Einstellung Effect, called functional fixedness. It’s a mental block against using a tool in a new way, even when it would solve a persistent problem to do so.

As an example, for years, I became so used to using spreadsheets for tracking data and making calculations, that I never thought to use them for other things. At the same time, I was trying all sorts of productivity apps to better manage my projects. I spent literally years trying out various apps, but they all fell short.

One day, a mentor of mine told me to lay out my list of projects in a spreadsheet, and review it every day. It was so simple, but yet so effective. And I never thought to use a spreadsheet for that.

But that led to creating my GTD spreadsheet. Which led to an article that went viral. Which led to a course that now helps thousands of people organize their lives and become more productive (and provides me with a bit of passive income).

How to Overcome the Curse of Expertise

Both the Einstellung Effect and Functional Fixedness are persistent problems that can keep us from solving problems and coming up with creative new ideas. But you can overcome them. You just need to establish some better habits.

Below are a few habits to help stave off the curse of expertise.

Habit 1: Use Pattern Interrupts

A great way to stop the Einstellung Effect in its tracks is to use a pattern interrupt.

A pattern interrupt is anything that changes the way something is going, or in this case, how someone is thinking. There are many different flavors of pattern interrupt strategies, but what they have in common is breaking from the norm.

When you find yourself faced with a problem, and the Einstellung Effect and Functional Fixedness loom, try one of the following:

- stare off into space

- close your eyes and let your mind wander

- get up and walk around for a while

- “sleep on it” by leaving the problem for an extended period of time, and coming back to it later

When you come back to look at the problem again, you might find that you’re more open to other possible solutions.

Habit 2: Check Your Assumptions

In the water jug experiment, participants became stumped at problem 8 because they made a key assumption. They assumed that they solution would be the same as the one they had been using. That assumption blinded them to finding another way to try to solve the problem. And many participants gave up.

If you want to overcome this kind of blindness, you need to check your assumptions early on. You can do this by stopping to ask yourself two questions:

- what pervious problem are you assuming this problem is like?

- in what way is this problem different from that previous problem?

Focusing on how this problem is different should kick-start a different approach. You should begin looking elsewhere than your past experience. As a result, your proposed solutions should be a bit less biased toward your expertise.

Habit 3: Think of a Ridiculous Idea

A great way to shake yourself out of a fixed way of thinking is to come up with a ridiculous idea. That’s right; start by thinking of crazy stuff that seems like it’d never work.

When you’re facing a tough problem, force yourself to come up with a ridiculous idea that has no basis in your previous experience. Then spend some time thinking about how that idea could be a solution.

Don’t focus on trying to solve the problem, rather, focus on trying your best to see how this ridiculous solution could possibly solve the problem. As you see clear ways it would fail, take note of them.

What this does is force you to look at the different parts of the problem. When you think about something you would otherwise dismiss, you’ll likely have to approach the problem from a different angle. You’ll most likely start thinking about it differently.

Wrap-up: Beware of Expertise

Abraham Luchins showed something important with his water experiment. Our minds are subject to two dangerous cognitive biases: the Einstellung Effect and Functional Fixedness.

For all of the positive things about expert experience, it can also train us to stop being creative and innovative. Expertise can be more of a barrier than it is a helpful tool.

So should we all stop gaining experience and knowledge? No. But what we do need to do is stop leaning on our expertise. Past experience can be a good indicator to help us make sense of the present, but not always. Sometimes, it can actually make it more difficult for us to make sense of the present.

Using pattern interrupts, checking assumptions, and thinking of ridiculous ideas are three tools that can help you avoid the curse of expertise. So while you gain experience and knowledge in a given area, you can also avoid having it become a drawback.