Understanding the psychology of feeling stuck and powerless, and how to address problems more effectively

Photo by freestocks on Unsplash

In 1972, Martin Seligman published a paper in which introduced a troubling psychological phenomenon. It explains why a lot of well-meaning people get stuck in bad situations. It’s the reason why we find ourselves feeling unable to change our circumstances. It’s what keeps us from making changes, getting creative, and innovating.

The phenomenon is called learned helplessness.

Seligman demonstrated it with a simple experiment. He set up a room in which dogs were given shocks, but as soon as they crossed a designated barrier, the shocks would stop. Those dogs quickly learned why the shocks were happening, and learned that they could prevent them. They stopped crossing the barrier.

But a second set of dogs was given the same training, but before that, they had been given random shocks that they couldn’t control. Those dogs were shown to be significantly less likely to learn how to escape the same shocks as the first group. Because of the prior random shocks, they didn’t learn that they could prevent shocks by crossing the barrier.

The only reasonable explanation for what Seligman saw was that an exposure to random, uncontrollable pain predisposes a dog to think that other instances of pain are also uncontrollable. Essentially, the dogs were conditioned to believe they were helpless.

Learned Helplessness

The behavior that Seligman discovered in dogs also happens in humans. We experience our fair share of pain, and we often don’t grasp its causes. So we’re conditioned to feel helpless. We train ourselves to stop trying to do anything. Like the second group of dogs in Seligman’s experiment, we accept the suffering and give up.

But how much of our suffering are we really helpless to change?

Of course, some pain, loss, anxiety, and other negative emotions are both random and uncontrollable. But much of it is not — at least not to the extent that we think it is. More of our suffering is within our control than we think. But until we come to some crucial realizations, we’ll continue feeling that our suffering is something we’re doomed to suffer.

Separate Events From Experiences

The ancient Greek Stoics pointed out that there is a difference between events and how we experience them. Our naive way of experiencing negative things is usually something like this: this day has been terrible; all of these bad things happened to me!

But the Stoics would tell us that we’re overreaching. It’s not that the day or the events are bad. The events that happen every day are neutral. They’re simply the workings of the world and its people. What makes events good or bad are our experiences of them.

We humans almost automatically form desires and expectations. We want things to go a certain way. We want people to act in certain ways. We invest emotional energy in hopeful anticipation of how things will turn out.

When things don’t turn out the way we desire, we get disappointed, upset, or sad. But if we hadn’t invested as much emotion in how the events of the world panned out, our emotional reaction would be different. That is to say, if we hadn’t invested so much emotional energy in an outcome up front, we wouldn’t lose so much when things didn’t work out.

Separate Pain From Suffering

Another related distinction is the one between pain and suffering. Pain is a sensation. It’s what happens automatically when you receive some sort of trauma — be it physical or mental. Pain just happens. We can’t control it.

Suffering is different.

Suffering is the anguish that often comes when we encounter pain, and let it build into a bunch of negative emotions. It comes from the “why me?” or “this isn’t fair!” response to pain or other undesirable feelings. We desire pleasure or think we deserve pleasurable feelings all the time. So when we feel pain, we can often become frustrated, angry, then anxious, then hopeless. That’s suffering. But it’s something we can learn to prevent.

Your Mental Energy is an Investment

At a basic level, Stoicism is a philosophy of wise emotional investment. Don’t put in what you can’t afford to lose, and you’ll stay relatively happy. The suffering and helplessness we feel comes from losing a large emotional investment. Stoicism reminds us not to invest so much in things we don’t control. In a word, it’s detachment.

But the key of Stoicism isn’t to completely detach from the world. It’s simply to remember that like time or money, your mental energy is something you can invest or save. And like any investment, it carries the risk of loss.

The best way to avoid losing your mental energy is to invest more wisely. Be picky about what you invest your emotional energy in. Here’s a simple criterion to help you guide your mental energy: focus on what you can control or influence. Let go of what you cannot.

Stay In Your Spheres

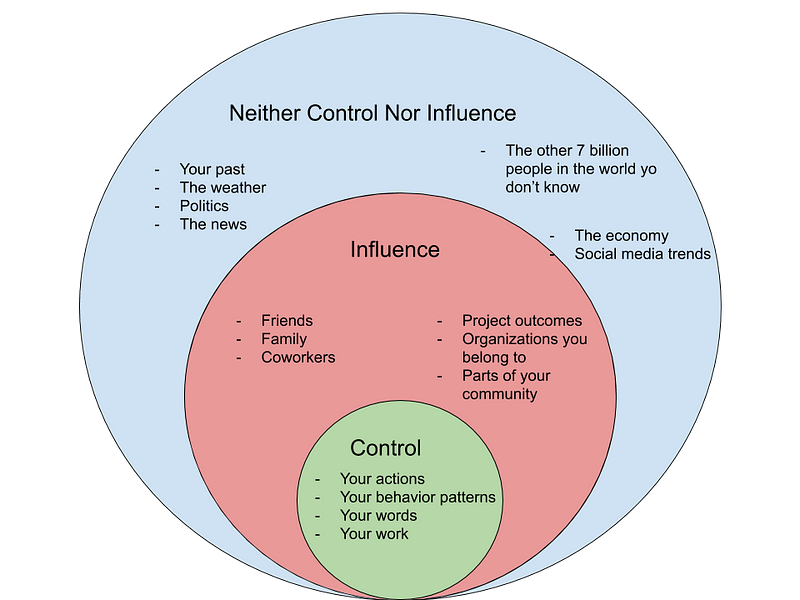

The term “sphere of influence” is used in numerous disciplines — from politics to business. But the idea is simple and useful for daily life. There is a small set of things over which you have significant influence.

image c/o the author

Notice that the term used isn’t control, but rather influence. You can only control your non-immediate reactions to things and your behavior. But outside of that, while you don’t have control over other things or people, you do have influence. You can do things that, depending on other factors, may serve to tip the scales toward your desired result — but that’s as much assurance as you’ll get.

Outside of the spheres of control and influence is, well, the rest of the world. And while it can be fun or educational to learn and wonder about it, you probably can’t influence it, and you definitely can’t control it. So to invest much of any of your emotions into it is wrong-headed, and will likely lead to suffering.

Focus as much of your mental energy as possible in the sphere of control. Focus less of it in your sphere of influence. Focus as little mental energy as possible in the outermost sphere you can neither control nor influence.

When you stop investing mental energy outside your sphere of control, you’ll stop feeling helpless. Rather than wondering how you’ll get out of this terrible situation, you’ll remember that there’s much of the situation you can’t control. Then you can focus on your innermost sphere — where you can work on your own self-talk, mood, and behavior.

So long as you can choose to invest more mental energy on things you can control — namely your thoughts and behavior — you’ll never feel helpless. Remember that you’re an investor. Choose to invest your mental and emotional energy wisely.