And Need Them Badly

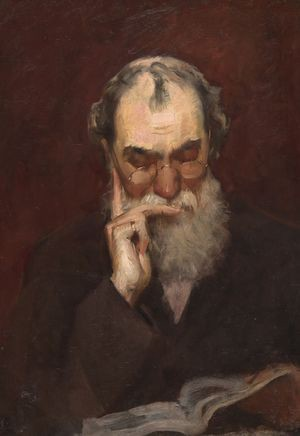

“Philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.”

-Karl Marx-

When I first elected to take up philosophy as a vocation, I was 19 years old. My reasoning was sound (for a 19-year-old): I loved reading and writing about philosophy, and I aimed to make doing it my career. The problem is this: with few exceptions, the only way to do this is to stay in the academy — teaching the subject as a professor, and performing the requisite academic duties as well. When I was 19 I was quite cynical about the business world, so the prospect of segregating myself from it seemed perfect. I craved the insular environment of the academic setting, and I looked forward to spending my entire working live in a scholastic Shangri-La.

For reasons that I’ve addressed elsewhere, I recently closed the door on that career path, after a long and arduous bout of soul-searching. But as I began my career in the non-academic world that I had initially viewed as an interim affair, I came to ask myself if I really couldn’t bring my scholastic tendencies into the business world.

Going Public

There have been movements aimed at bringing philosophy into the public, aimed mostly at counseling or otherwise educational or therapeutic purposes for individuals, with some tangential mention of being involved in business. I firmly believe that philosophy can and should play this part for individuals — that’s why many philosophers did their work in the first place.

What I want to advocate, though, is for a bigger push — by philosophers — to integrate philosophical thinking into businesses. Specifically, in an age of startups, socially conscious firms, and the emphasis of both “culture” and “core values”, I believe that the business environment is ripe for the insertion of philosophers among those consulting and strategizing for and with them.

When a business is beginning, often times its struggles are existential in nature. Consultants can come in and teach you the finer points of agile, scrum, kanban — you name it. Accountants can come in and teach you how to make sure you don’t lose track of your money. But precious few can come in and tell you what your business is really going to be at a deep level.

But that’s the kind of stuff philosophers are trained to do. They look for essences. They probe, pull apart, and split hairs. They are trained to be skeptical until something like certainty and precision are reached.

I don’t recommend this “big push” out of the clear blue sky; I’ve been living it for the past 5 years. Around the time I completed my MA in philosophy, I took a job at a small(ish) company that does industrial supply, engineering, and logistics — which doesn’t sound like the most welcoming of such a seemingly esoteric discipline as philosophy. But lo and behold, a half-decade later, and my having moved up in the company is a direct result of my having employed the tools that I smuggled in from my training in philosophy.

Hire Some Philosophers

Philosophical training allows for a certain kind of speculation (what Alfred North Whitehead called “speculative philosophy”). Speculation is characterized by its freedom. But in every discipline, speculation, and the characteristic freedom is usually limited by whatever the foundational principles are of that discipline. Philosophy, on the other hand, really has no foundational principles. In fact, its modus operandi involves questioning the foundational principles of all of the other disciplines.

It would seem, then, that those who are heavily steeped in philosophical practice in the academy are more likely to employ that kind of foundation-free speculation — the kind that takes no idea or limit as set in stone. This is where innovation is most likely to come from.

Outspoken philosopher Samir Chopra recognizes this as:

Descriptions like this of philosophy abound. If anything characterizes philosophy as a discipline and a practice, it is the refusal to accept dogmatic thinking — to accept what other disciplines assume to be true. There is no agreed upon approach to coming up with a theory in philosophy, but there is an agreed upon reception of any theory: ask questions and attempt to falsify a given theory. When done properly, this isn’t antagonistic in nature, merely an attempt to make sure that any theory offered up is backed by sound reasoning.

To recap: philosophical thinking rests on two core principles:

- There are no boundaries or limits to what can be explored, questioned, and theorized about — nor are there limits to how.

- Each new idea is addressed on its own terms and held up to rigorous questioning.

Does this ring a bell to those in the business environment? It should, it’s practically a description of the ideal brainstorming practice. Brainstorming is embraced by so many businesses because it leads to innovation (when done correctly). Innovation is more highly valued now in the business world (or at least more talked about) than ever before, so if philosophy breeds the kind of thinking that leads to innovation, it seems that those who do philosophy well have a leg up on innovation.