A 3-part Blueprint for Making the Most of an Hour of Reflection

As the legend goes, George Shultz — who was Secretary of State under President Ronald Reagan — would take an hour each week to lock himself in the office with only a pad of paper and pen. No interruptions, no tasks at hand to work on, just thinking. The aim was simply to steal some time away from the din of activity that makes up most of the week, and spend some time in deep reflection.

The practice is similar to David Allen’s suggested practice of a weekly review — where you review all of the “stuff” parked in your personal productivity system to understand what needs attention and what doesn’t. Shultz himself apparently only had a pad of paper and a writing instrument. He would sit with those simple tools and reflect — make sense of the things that happened, and things that had yet to happen. It often began simply by being alone with his mind, and allowing it to go wherever it went.

That kind of unstructured mental activity taps into what psychologists call the default mode network — a network in the brain that goes to work when the mind is not directed at a specific purpose. It has been talked about synoymously with day-dreaming or “zoning out” But it’s much more nuanced than that. In fact, the default mode network has been shown to be responsible for processing the various events that have taken place in one’s life, and making sense of them — assigning meaning, and making connections.

Taking time to leverage this default mode network — to let the mind settle and wander away from specific tasks — can yield much more value than trying to put it in a stranglehold of focus. That is at the foundation of the Shultz hour: get away from the two biggest stressors on your mind that can sap productivity:

- bombardment by external stimulus (emails, calls, “urgent” issues) and

- forced focus (as in: “I need to force myself to just do this damn task).

Structuring the Shultz Hour

Here I lay out a way to straddle that line between freedom and focus, between spontaneity and structure — to take one hour per week and squeeze the juices of peak productivity out of it. Think of the results of this Shultz hour like orange juice concentrate: it may look like just a little bit, but it’s strong enough to provide the basis for 5x its volume in juice. In the same way, spending 1 hour reflecting and prioritizing — when done correctly — can provide the concentrated power of decisiveness and clarity of vision that will power you through the trials and tribulations of the remaining 167 hours of the week.

Here are a few best practices in constructing a Shultz Hour of your own. They are guideposts, meant to be followed only inasmuch as they prove productive for you. The goal of the Shultz Hour is simple: to spend an hour with little to no distractions, and end the hour feeling way more in control of your where your life is going. Measure everything about the hour against that yardstick, and adjust accordingly.

1. Clear Your Mind Through Journaling

We spend all week attempting to bury many of our thoughts, and this is usually helpful in getting us to focus on what we’re trying to work on. But those thoughts don’t usually go away on their own. They’re in your head for a reason, and unless that reason is addressed, they’re likely to stay there — which can only serve to sap your mental capacity.

In fact, psychologists have a name for these things rattling around your mind: unconstructive repetitive thoughts. They’re defined as negative thoughts that occur frequently and involuntarily, while distracting from other cognitive activities. Some studies point to a cognitive decline — both in the short and long term — from the continued presence of these URTs.

The first step in getting into a more reflective mode is to gather as many of these URTs as possible, and lay them out in front of you — on paper. A great way to do this is to simply sit and try not to think of anything — like you would during meditation. Inevitably, you’ll have thoughts and feelings. As they come, simply record them, then move on. Do this for 5–10 minutes, or until the URTs are not coming to you as quickly.

By the end of this exercise, you should have an array of thoughts, feelings, obligations, worries, doubts, etc. The first time you do it, there may be a lot of them. In subsequent instances, there should be fewer of them, but still enough to move on to the next exercise.

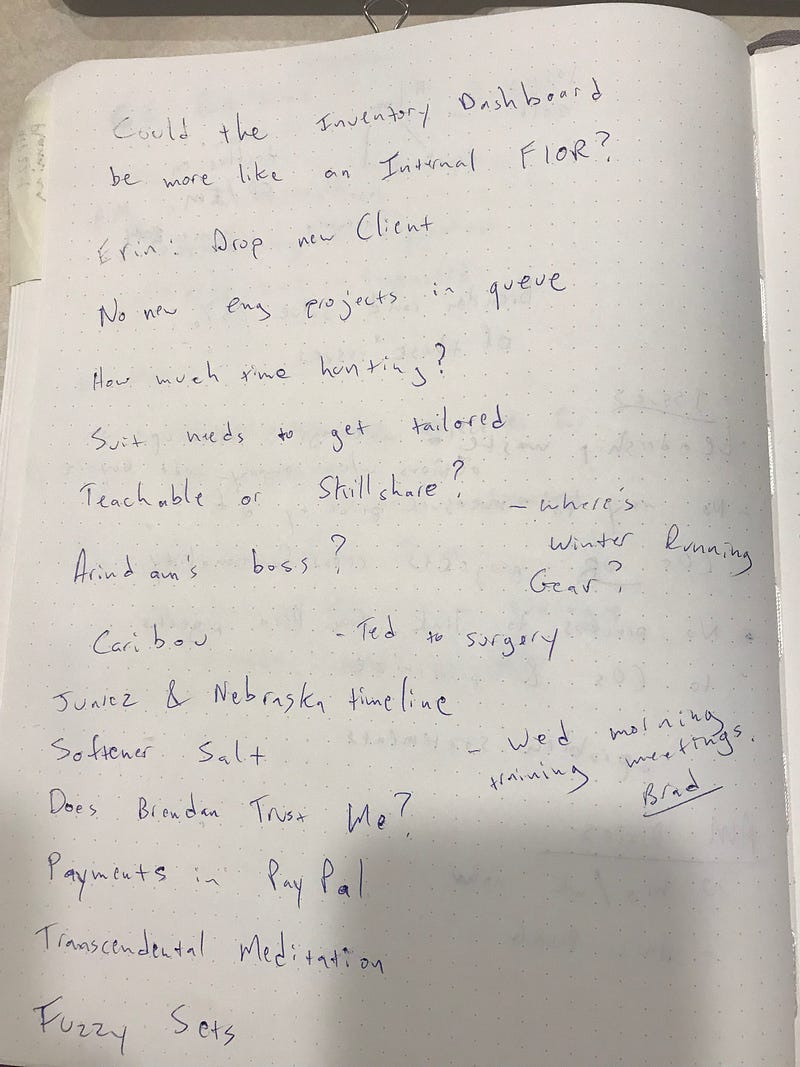

Your initial run-through might produce quite a bit of stuff. Keep rolling as long as things keep coming to you. I tend to aim for about 1 notebook page. Here’s a pull from one last month:

As you can see, there’s quite a mix of stuff. Things I feel the need to do, questions that are on my mind. People to touch base with, etc. Most of these don’t relate to open projects on my list. They may end up there after a session, but that’s not the goal. The goal is to get it recorded, so I can extract meaning from it in the next two steps.

2. Reflect On Your Relationships

If you look at the majority of the URTs you have, most of them will originate from a relationship of some kind. There are two kinds of relationships:

- intrapersonal (the one you have with yourself) and

- interpersonal (the ones you have with others)

Both are important, and both create stress that affects your cognitive ability and productivity. You need to be able to devote the time and energy to build and sustain those relationships — which is what this second part of a Shultz Hour is all about.

Relationships consist of three major things that push and pull at us: desires, expectations, and commitments. We desire things of ourselves and others, and they desire things of us. We expect things of ourselves and others, and they expect things of us. What is perhaps the most important: we commit to things — both to ourselves and others, and we perceive that others have committed things to us.

Many of the things on your list of thoughts from the first exercise will represent one of the three components of a relationship, or will be the direct precursor to one. In other words: when you try to relax and not think of anything in particular, your mind will likely express the stress it’s under through a repetitive involuntary thought — which is likely the expression of some desire, expectation or commitment it perceives.

From that list of thoughts, examine them through the following lenses:

- To whom in your life do they relate?

- What do they represent: a desire, expectation, or commitment?

Really challenge yourself here. Even emotions are often related to some desire you have — and if it’s a desire, it’s usually of someone, or a group of people. - Everything that doesn’t seem relate to those 3 things, put it aside for the time being.

With a list of desires, commitments, and expectations in tow, begin to look at whether the desires commitments, and expectations match up with each other for each person, and each topic.

For instance, I have a question in my page shown above about how much time I should spend hunting — meaning how much time do I need to allocate at my day job for finding and trying to land new customers. I’m new to the sales role in general, and that wasn’t made clear to me. So it’s on my mind, and it’s been bugging me in the background. Taking the above questions, I formulate how it fits in to relationships in my life:

- Who: me, my direct manager, the director of sales, my team

- What: expectation from director of sales, but it’s not clear what that expectation is. My manager is okay with me going slowly and working on current customer relationships, as well as managing my team. However, the director of sales sees me as a new resource to work toward our aggressive sales goal. If I can’t do that right away, I need to work to manage that expectation. His desire will likely always be that I devote significant time to hunting new prospects, but the expectation needs to be managed.

In essence, if there is a mismatch between what people desire from one another, expect from one another, and what has been committed to, there is some stress in the relationship. The same is true intrapersonally. If there is any mismatch in your desires of, expectations of, and commitments to yourself, then your relationship with yourself will be strained.

With a clear vision of what the desires, expectations, and commitments are that are on your mind — as well as how in sync they are — you should get a sense for goals and actions related to them.

3. Commit To Creative Solutions

You have now dumped as much of the nagging thoughts and feelings from your head as possible, outlined the inventory of your relationships. Now it’s time to make sense of it all.

For me, this is the most invigorating part of the process. Specifically, in my relationships with coworkers, I see gaps in perception, in what’s desired and what’s committed to, and I can’t help but concoct a possible avenue to take in order to change things. I get creative, I gaze into space and think through how various scenarios might play out. I formulate a few actions to take over the week, and see what they do.

Following the example above, I decided that I’d make it a point to bump into the director sales the next time we were both in the office, and start a conversation. The simple goal would be to feel out what his expectations were of me — as well as what he’d relayed to the leadership of our company. Then, I’d drop some hints about what my current workload was like, and what I believe are reasonable expectations. I was able to do that, and it made me feel a whole lot better. In subsequent sessions, no questions or concerns came up as I dumped my nagging thoughts out on paper.

I offer a process here, but the key is this: stay unencumbered. Don’t look at your task list, open projects, or anything else. Focus on what came out of your mind during this session. There will be new stuff — important stuff — that wasn’t on your official to-do list. That’s probably because some of the most important stuff we should be doing scares us to death when we put it on an official to-do list. That’s because we haven’t thought it through — how it relates to other priorities and relationships in our lives, or what it means to us. Here’s your chance to do that.

Though this is the final step, it is the beginning of another cycle. Your plans contain hypotheses, which you test by carrying them out. If they blow up, then you didn’t have a complete understanding of the situation. You reflect on that this week. You think about what you might have missed, form new hypothesis — lather, rinse, repeat. It is the seedbed of personal growth, and so long as you keep watering it, the saplings should continue to sprout.