And, How Do You Go About Doing It?

Among the most well-worn phrases in the business world is “thinking outside the box”. It is supposed to mean thinking creatively, freely, and off the beaten path. It’s the kind of thinking that — in an age of increasingly powerful algorithms and neural networks — garners significant attention. For now, it’s the kind of stuff that machines can’t do that well.

One supposed story of the term’s origin is actually a great illustration (literally) of what this kind of thinking is, and why it’s so sought-after. As the story goes, management consulting groups in the 1960s and 70s began using a particular puzzle called the “nine dots puzzle” from a 1914 book by Sam Lloyd called the Cyclopedia of Puzzles. They would present the diagram below, with the following instructions:

Link all 9 dots using four straight lines or fewer, without lifting the pen and without tracing the same line more than once.

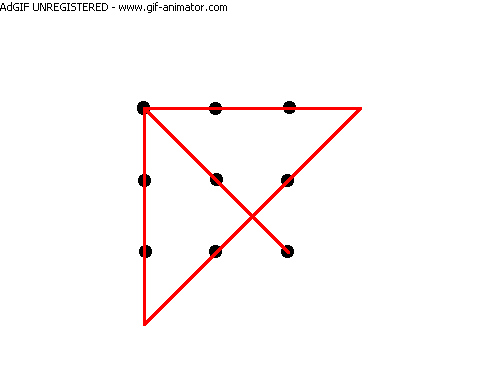

The most oft-cited solution appears below. It uses only 4 lines.

See where “outside the box” comes from? There was no directive given about staying within a box, but our minds tend to build a box there, and a constraint is instantly put in place.

Thinking outside the box is about dispensing with constraints — as many as possible. That’s what the solution above does, and that’s what the most effective kind of original and innovative thinking also does.

Below are 3 strategies that can help you think “outside the box”— in the way that the origin of the term suggests.

1. Eliminate the Goal-Directedness of Your Thinking

If you aim at the same target everyone else is aiming at, your shots will end up where everyone else’s do. If you till the same soil that everyone else tills, plant the same seeds they plant, and use the same water, you’ll get the same garden.

My point is that the minute you introduce a goal in your thinking, you’re introducing a constraint. Your mind now has a direction, and it will tend to go in that direction. This is why so many businesses bring in outside consultants to help come up with new ideas. The consultants don’t carry the burden of constraints on their thinking. They can dream up and offer up wildly new ideas that get people excited, and lead to innovative pivots and launches.

This has become a hot topic in child psychology. A 2014 study at the University of Colorado studied the effect that free play and structured play has on children’s executive function — the ability to independently set and work toward goals. The findings:

The results showed that the more time children spent in less structured activities, the better their self-directed executive function. Conversely, the more time children spent in more structured activities the poorer their self-directed executive function.

You’re not a child, of course, but think about how structured thinking — as opposed to unstructured thinking — can have a similar affect on what crazy new ideas you’re able to come up with.

2. Intend to encounter, rather than “come up with” ideas

Rather than “coming up with ideas” — which is more an act of creation, it’s better to think of yourself as just encountering ideas. You’re not creating, you’re just browsing. That’s a real difference in attitude. You’d be surprised at the difference this can make. It takes a weight off your shoulders to not have to make something, but rather to just stumble upon it.

Think of it as walking through an open-air flea market, looking at whatever trinkets you happen to see. You can move with ease — not particularly moved by any of them until something really stands out. But if there are items in that same flea-market that you hand-crafted and brought there, you will naturally pay more attention to them.

Also, if you find that you’ve got an idea that’s pretty stupid, if you don’t view yourself as having created it, you’re less likely to be emotionally and cognitively impacted by a negative assessment of it. You can keep on churning out ideas.

3. Think wide

Keep every realm of thinking on the table. Geography, religion, finance, cubist painting, archaeology. Don’t discount anything as unrelated or unconnected. It is often that kind of thinking that creates the kind of problems that demand “outside of the box” thinking in the first place.

One of my favorite stories in this spirit is about Allan Lichtman. He’s the guy who has become notorious for establishing a system that predicted Donald Trump’s unlikely election as president in 2016— when even seasoned political scientists and statisticians couldn’t. It also predicted every presidential election result since the system was published in his book in 1981.

Endgadget ran a great piece about how he did it:

“Lichtman’s prediction system is founded on geophysics, using the fundamental ideas of earthquake science to predict social and political disruption. He created the Keys to the White House system with Vladimir Keilis-Borok, founder of the International Institute of Earthquake Prediction Theory and Mathematical Geophysics, in 1981. Essentially, Lichtman and Keilis-Borok changed their thinking about elections. They applied geophysical terms to the process, getting rid of ideas like Democrat, Republican, liberal and conservative. Instead, they reinterpreted the system in terms of stability and upheaval.”

Did you catch that? Lichtman’s collaborator on a prediction system for political elections was a geologist studying earthquakes.

The lesson here? Stay wide in your thinking. Don’t discount things that seem unconnected. The benefits to your thinking can be tremendous.

Did you find value in this piece? Consider subscribing to my weekly newsletter — Woolgathering. It’s one email per week, with great ideas to add value to your life and work.