A simple practice to boost intelligence, avoid cognitive bias, and prove your own ideas wrong

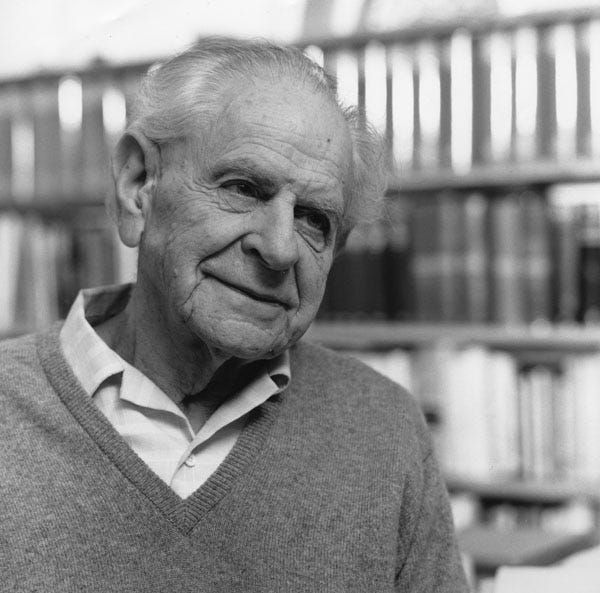

In the middle of the 20th century, philosopher and professor Karl Popper found himself mystified by the beliefs and methods of the otherwise intelligent and rational people around him.

I found that those of my friends who were admirers of Marx, Freud, and Adler were impressed by a number of points common to these theories, and especially by their apparent explanatory power. These theories appear to be able to explain practically everything that happened within the fields to which they referred. Once your eyes were thus opened you saw confirmed instances everywhere: the world was full of verifications of the theory. Whatever happened always confirmed it.

That last sentence should ring some alarm bells for many readers — it’s a very simple description of confirmation bias. Basically, when you gain a perspective or theory, you tend to interpret everything as confirming that idea. Whatever seems to contradict it is tossed aside or somehow contorted to fit our beliefs.

Popper saw this problem inherent in many theories — both in the physical and social sciences, and in other realms as well. After all, if we find evidence that seems to contradict our beliefs, we should be stopping to see if perhaps we need to abandon or modify our belief.

As a way to cure this ill of self-confirming theories and belief systems, he came up with what is now called falsificationism: the idea that a theory or belief system can only be scientific if it clearly lays out what specific evidence would prove it wrong.

Basically, if you’re going to claim that you know something, you have to be willing to admit that you could be wrong about it. More than that, you have to lay out what kind of evidence would prove you wrong. You have to make yourself falsifiable.

Why is falsification important?

My suggestion is that the spirit of Popper’s principle can help us become smarter and make better decisions — in both professional and personal realms. Adopting an attitude of falsifiability does a few key things:

- it helps you to avoid many cognitive biases that can hinder intellectual growth and good decision making

- it makes you a clearer thinker by forcing you to be specific about what you think you know, and what evidence you have

- it boosts your creative thinking by making you naturally more receptive to new ideas and helping you more quickly process them

Our minds tend to run headlong toward safety and comfort. This is true with regards to physical safety and comfort —but it’s also true of intellectual safety and certainty. If we feel like we know something for sure — like we have a firm grasp of it — we want to hold on to that feeling.

Because we want to hold on to that feeling, we tend to manufacture certainty by either stopping the search for new information (fearful that it might endanger our feeling of certainty) or interpreting new information in a way that keeps supporting our feeling of certainty.

Those practices stifles creative thinking, intellectual growth, and personal growth. Here’s how thinking in terms of falsification can help you avoid this trap.

Putting the falsification mindset into action

The falsifiability mindset is all about thinking through the implications of beliefs, judgments, and decisions. It’s about curbing your craving for certainty. Adopting this mindset is as easy as picking up a simple practice.

For the decision that you’re making, take out a clean sheet of paper, and draw a line down the middle.

On the left side, write at the top “What I Believe to Be True.”

On the right side, write at the top “What Would Prove Me Wrong.”

That left hand side could be anything. It could be something personal and low-stakes, like I should buy the new iPhone model or something more substantial, like global warming is the result of human industrial waste interacting with the atmosphere.

The right side is where you will have to do a bit of thinking. That’s where this practice can yield dividends. Having to understand what would prove you wrong forces you to do 3 important things:

- clarify what your actual belief is

- confronts the possibility that you could be wrong

- encourages you to tacitly commit to changing your mind under some specific conditions

My personal falsification story

One of my strongest-held beliefs was that in order to be professionally fulfilled, I needed to be a professor of philosophy.

At age 30, I was ready to take the final step on that path and apply for PhD programs. I also found myself with a newborn daughter, a mortgage, debt, and a full-time job.

I spent 6 months writing and preparing applications, and was accepted into 3 different programs with funding. All were far away from home. It was decision time.

My wife and I had always talked about doing this in the abstract. But now, we had a baby, a mortgage, bills, and jobs. No matter which of the 3 programs I went to, we’d have to move at least a thousand miles away.

I had been promoted twice at my 9 to 5 job. Meanwhile, the job market in academia — specifically in humanities and philosophy — was brutal. About 50% of PhD students didn’t finish their program. Of those that did, it took at least 4.5 years. Upon completion, a tenured position was as rare: about a 20% chance within the first 5 years, and almost always hundreds of miles from the school where one obtained their PhD. And the median salary for a professor of philosophy was just about what I was making at my 9-to-5 at the time.

I was aware of most of those facts. But I was so certain about my belief that as each of them came up in discussions with my wife, I did what Popper described: I manipulated my belief to dodge the gravity of the new evidence.

At one point, my wife asked, exasperated, what would make me re-think my zeal about this professional goal I had. It was a good question, and it seemed like I had never thought of it before.

So I broke out a piece of paper, put a line down the middle, and on one side, I wrote my belief:

In order to feel professionally fulfilled, I need to accept one of these offers from a PhD program, quit my job, and move my family across the country.

On the other side, I wrote: what would prove me wrong?

The simplest answer to that question was that I would be proven wrong if I could do work that made me happy — without upending my current life for a PhD program. But I was so sure there was no way that was going to happen. My wife asked me to try to prove myself wrong by looking for ways that this could happen, however crazy they may sound. This took considerable effort to do, but it was the most transformative exercise I have ever done.

I sat down with that piece of paper, and I forced myself to pursue evidence and possibilities that contradicted what I so firmly believed. How could I still be happy doing anything else but taking this opportunity I saw in front of me? Well, I could do all of the activities that attracted me to being a professor:

- thinking and writing about life’s big, interesting questions

- teaching others to do the same

- reading interesting and thought provoking stuff

Was there a way that I could do that stuff without cross-country move, the 4–5 years on grad school stipend, and the chaotic uncertainty of the academic job market?

The answer appeared to be yes.

I had recently started writing on the internet about the exact topics that I had always written about in the past. The online coaching and course-building phenomenon was already gaining traction. I could read and write about the interesting things I always enjoyed, as well as develop courses and teach others. And I could this without quitting my reliable source of income, moving my family across the country, or subjecting myself and my family to a brutal series of job hunts and inevitable cross-country relocations.

I began with a burning certainty in my belief. I challenged that belief by asking what would need to be true for it to be wrong. Once I wrote that down, I essentially committed to changing my initial belief if a certain condition was met.

By investigating what would falsify my belief, and whether those conditions might already exist, I was able to break out of the narrow mindset I had occupied for so long. By my calculations, it very likely saved me $400,000, along with saving immeasurable stress on my marriage.

How you can adopt a falsification mindset

Adopting the falsification mindset is simple. Like any exercise in thinking, it helps if you write it out, but that’s not totally necessary.

- For any belief you have, ask what it would take for you to change your mind

- Be specific about what evidence would make you change your mind

- Seek out that evidence, and be willing to change your belief if you find it

For me, this was a game changer for an important life decision. But it also works for smaller beliefs and judgments.

Just ask yourself how you could be proven wrong — about any old belief you have. Are you researching a big purchase? If so, what discovery would cause you to cancel the purchase? Are you working toward a professional goal? If so, what new facts or experiences would convince you that this is the wrong goal?

We all have lots of hidden biases that can be examined this way.

If you really adopt the mindset, you should be able to see that your attitude will change — you’ll be more open-minded, and less likely to be dismissive of others or other sources of information. And in doing so, you should reap some serious intellectual benefits.

👉The Better Humans publication is a part of a network of personal development tools. For daily inspiration and insight, subscribe to our newsletter, and for your most important goals, find a personal coach.👈